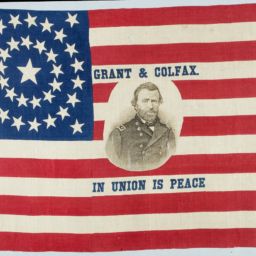

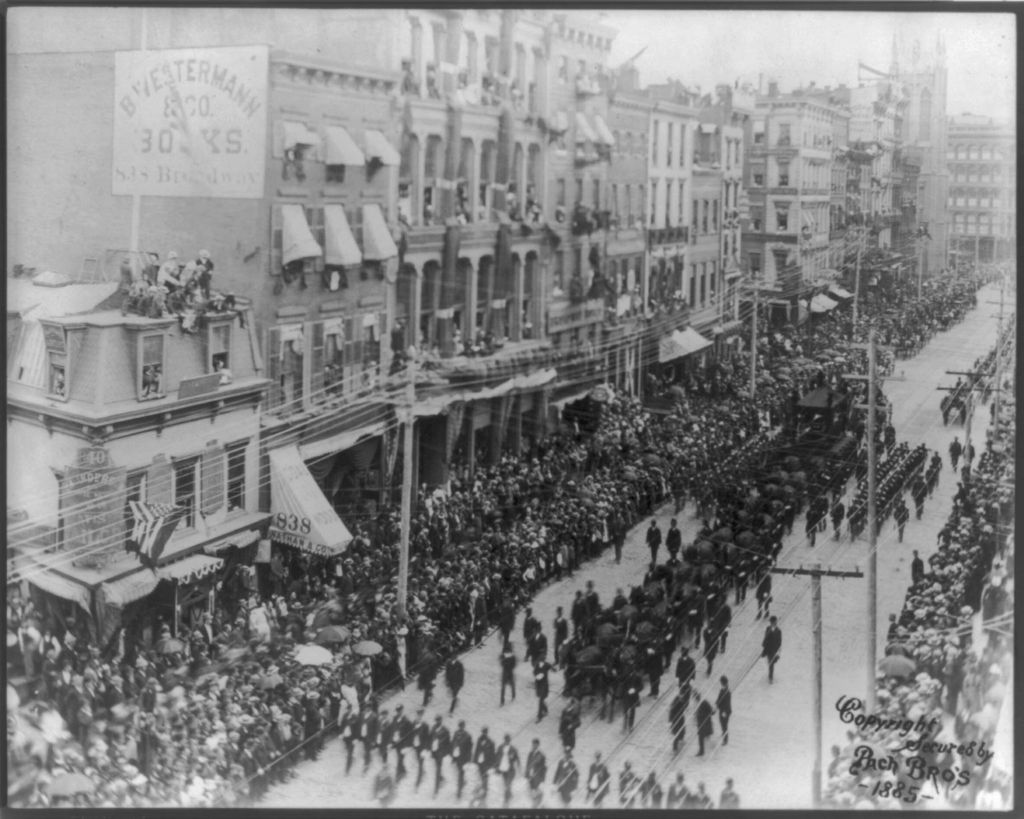

The then-largest public gathering in American history—some 1.5 million people—lined the streets of New York City on August 8, 1885, for the funeral procession of Ulysses S. Grant, formerly the victorious general-in-chief of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War and the twice-elected 18th president of the United States.

Actually, the day of mourning was nation-wide, even international, and not limited to New York City. As stated by LeBaron Bradford Colt, then judge of the U.S. First Circuit court, later to become a U.S. Senator, in a eulogy for U.S. Grant on the day of the funeral, delivered in Bristol, Rhode Island: “Today the country is one vast funeral train.” (White, 653)

In Grant, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Ron Chernow writes:

At 8:30 a.m. [in New York City] on August 8, [1885,] Civil War veterans hoisted Grant’s coffin to a waiting catafalque that had black plumes sprouting at each corner. Twenty-four black stallions, arranged in twelve pairs and attended by black grooms, stood ready to pull the hearse. Twenty generals preceded the horses, led by Winfield Scott Hancock, whose vanity Grant had mocked and who now sat astride a noble black steed. Every protocol for a military funeral was followed, including the riderless horse with boots facing backward in the stirrups. The funeral was a vast, elaborate affair, befitting a monarch or head of state, in marked contrast to the essential simplicity of the man honored. The grandeur emphasized the central place that Grant had occupied in the Civil War and its aftermath. “Out of all the hubbub of the war,” wrote Walt Whitman, “Lincoln and Grant emerge, the towering majestic figures.” (955)

Grant’s funeral procession got underway at 9:00 a.m., marked by the firing of a howitzer and the procession’s military bands beginning to play Franz Schubert’s dirge-like “Geisterchor,” (Chorus of Spirits), an adagio piece of incidental music from the play Rosamunde. But “at 9:30 a.m., thanks to arrangements made by Western Union, church bells pealed not only in New York, but across the United States at the same moment to usher in the day’s solemn activities.” (Picone, 69)

As Ronald C. White, Jr. observed in American Ulysses, “Some New Yorkers vividly remembered mourning Abraham Lincoln twenty years earlier, as his body passed through the city on the funeral train that would carry it to its burial in Springfield, Illinois. But while Lincoln’s death, coming at the very end of the Civil War, evoked more sadness in the North than in the South, Grant’s death prompted a full-scale national outpouring of grief and homage.” (White, 653)

Louis L. Picone, in Grant’s Tomb: The Epic Death of Ulysses S. Grant and the Making of an American Pantheon, notes:

An impressive 60,000 people marched, including 8,000 city workers led by Mayor Grace, dozens of military units, and 18,000 members of the Grand Army of the Republic. They included Marines, Navy, National Guard, Fort Sumter veterans, the Old 79th Highlanders with bagpipes in hand, and regiments from as far away as California. Some carried instruments, some held armaments, and some had howitzers or Gatling guns. But it was not a haphazard affair, and each unit marched lockstep in formation, and in full regalia, behind officers on horseback. The impressive spectacle of military forces was the largest ever gathered in United States history in peacetime. (70)

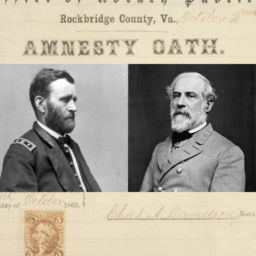

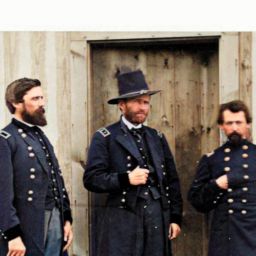

The honorary pall-bearers for the funeral included former Confederate generals Joseph E. Johnston and Simon B. Buckner as well as former Union generals who served with Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip H. Sheridan.*

“Congress and statehouses across the country emptied out to pay homage, sending fifteen U.S. senators, twelve congressmen, eighteen governors, and ten mayors to pay their respects. From city halls across America eight thousand civil and municipal officers converged to participate in the march.” (Chernow, 956)

The column of mourners who accompanied Grant’s body from City Hall in Lower Manhattan to a temporary tomb in Riverside Park, near what today is West 122nd Street, was seven miles long. “All along the route, sewing girls, apprentices, and clerks hung bands of black and white, flowers, and flags from windows. Toward the end of the route, an African American bootblack had nailed up a sign in front of his workstation: ‘He Helped to Set Me Free.’” (White, 656)

When the procession, heading up Fifth Avenue, passed the Fifth Avenue Hotel at 23rd Street, it was joined by none other than President Grover Cleveland, Vice President Thomas Andrews Hendricks, and former presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester Arthur. (Picone, 71)

At West 72nd Street, the procession turned and headed northward on Riverside Drive, at which point warships on the nearby Hudson River began to boom their salutes. (White, 656)

By midafternoon, the procession reached Grant’s small, temporary brick tomb, where a bugler blew taps. William Tecumseh Sherman, a colleague of Grant’s during the Civil War and Commanding General of the U.S. Army after the Civil War, “stood ramrod straight, his body shaking with tears.” (957)

Placed in a temporary tomb in Riverside Park, “Grant’s body stayed there for nearly 12 years, while supporters raised money for the construction of a permanent resting place. In what was then the biggest public fundraising campaign in history, some 90,000 people from around the world donated over $600,000 to build Grant’s Tomb.” (American Experience)

The New York Herald wrote in their publication shortly after Grant’s death that “he had his faults, who has not? We cannot see them because the brilliancy of his deeds shines in our eyes.” (National Park Service)