On August 5, 1861, Congress approved President Abraham Lincoln’s July 31, 1861, request to designate to brigadier generalships more than two dozen men, including Ulysses S. Grant.

Various members of Congress had submitted names to President Lincoln first. Grant’s inclusion in the list was based on the recommendation of Republican U.S. Representative Elihu Washburne, a resident of Galena, Illinois, where Grant also resided and worked—at his father’s leather goods store as a clerk—at the time that the Civil War erupted (Bonekemper, Lincoln, 33). The commission was retroactively effective May 17, 1861, and made Grant 35th in seniority in the U.S. Army, which at that time was headed by Brevet Lieutenant General Winfield Scott (Bonekempter, Grant, 509).

Since June 14, 1861, Grant, as a colonel, had been commanding the 21st Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry, (which had previously been named the Seventh Illinois Infantry Regiment). It had been mustered into service only a few weeks before that time, and Grant brought to it badly needed order and discipline, including during a period when the regiment was camped in the town of Mexico, Missouri. Missouri suffered a population profoundly divided by the Civil War, perhaps more so than any other state in 1861, and Union Army units and pro-Confederate forces were in open, armed conflict within Missouri.

Grant writes in his Personal Memoirs:

My arrival in Mexico had been preceded by that of two or three regiments in which proper discipline had not been maintained, and the men had been in the habit of visiting houses without invitation and helping themselves to food and drink, or demanding them from the occupants. They carried their muskets while out of camp and made every man they found take the oath of allegiance to the government. I at once published orders prohibiting the soldiers from going into private houses unless invited by the inhabitants, and from appropriating private property to their own or to government uses. The people were no longer molested or made afraid. I received the most marked courtesy from the citizens of Mexico as long as I remained there. (252)

After the Congress made the President’s selections official, Grant got word of his promotion in a roundabout way. Professor Brooks D. Simpson in Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, writes:

One August morning when the regimental chaplain [James L. Crane] arrived with the morning paper from St. Louis, Grant was shocked to read that he had been promoted to brigadier general of volunteers. “I had no suspicion of it,” he told the chaplain. “It never came from any request of mine. It must be some of Washburne’s work.” And so it was. Lincoln had instructed Illinois’s congressional delegation to offer four names for promotion in an ordered list. The congressmen met and discussed several names. . . . All were more prominent than Grant; all therefore had enemies as well as friends. Washburne, using both his political clout and the fact that there was no strong opposition to Grant, advanced his name to the head of the list. (114–115)

Ron Chernow in Grant writes:

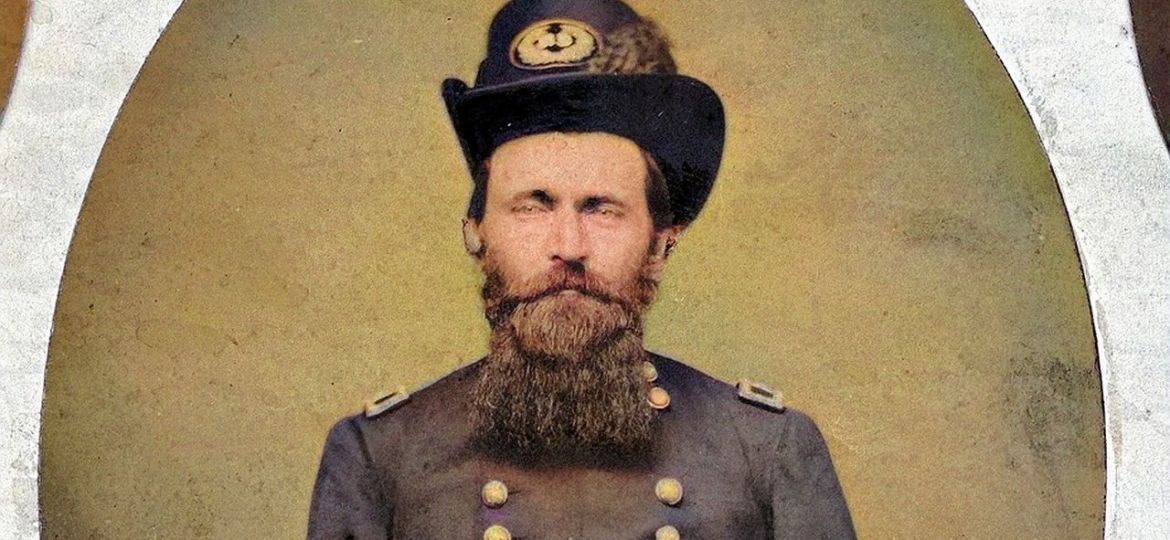

Crane was amazed by Grant’s unflappable response as “he very leisurely rose up and pulled his black felt hat a little nearer his eyes . . . and walked away about his business with as much apparent unconcern as if some one had merely told him that his new suit of clothes was finished.” For Grant it was a dreamlike transformation: the man who had recently toiled as a store clerk, who had felt cursed by fate, who had lobbied wearily for appointment as a colonel, had been unexpectedly bumped up to brigadier general in charge of four regiments, or about four thousand men, without having fought a single battle. And in the end he required political pull to do so. After years of wandering, Grant had popped up in the right congressional district in the right state. (142–143)

As Ronald C. White, Jr. notes in American Ulysses, “seven years earlier, Grant had resigned [from the U.S. Army] in dishonor,” but now Grant saw himself listed in an edition of the St. Louis Democrat as seventeenth of thirty-four new brigadiers. Now, “he was entitled to wear a star on each shoulder” and would need to “order a general’s uniform with two parallel rows of brass buttons.” (155)

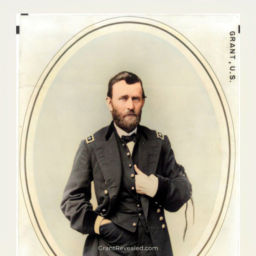

IMAGE

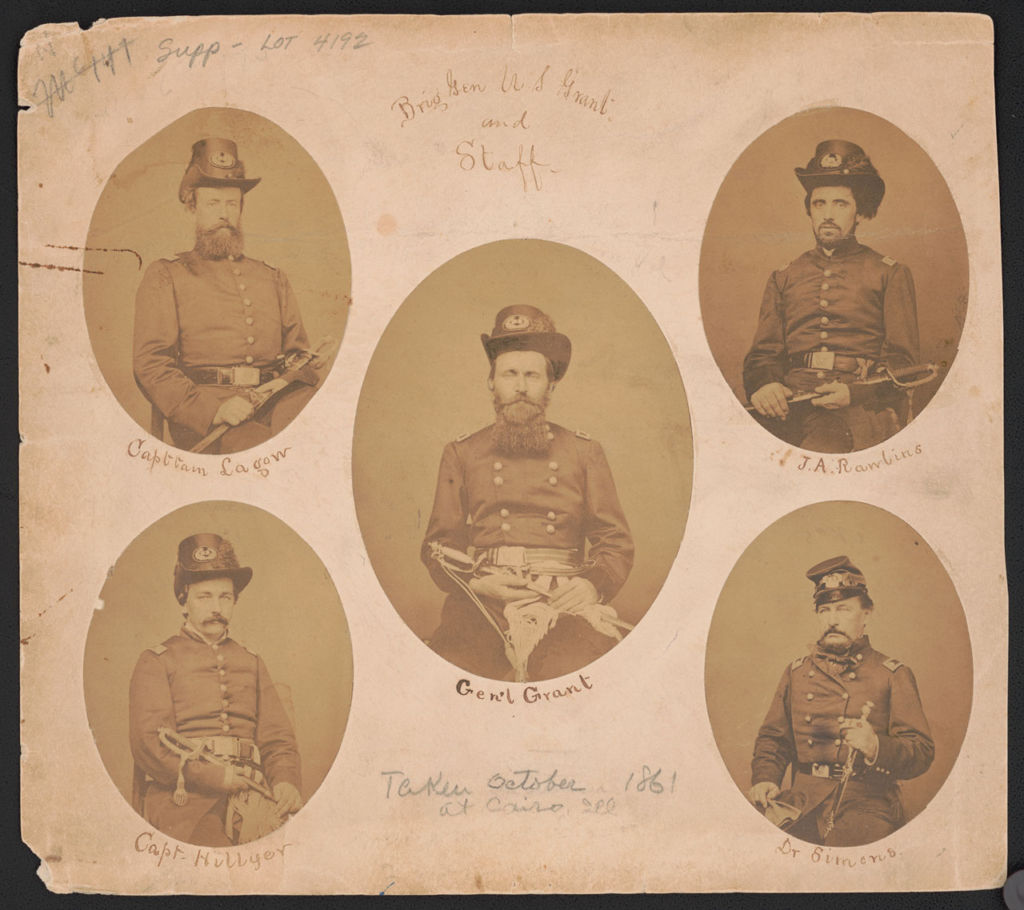

Brig. Gen. U.S. Grant and staff Captain Lagow, Gen’l. Grant, J.A. Rawlins, Capt. Hillyer, Dr. Simons, Oct. 1861. Cairo, Illinois. Montage: five photographic prints on one mount. Shown are Ulysses S. Grant surrounded by Clark B. Lagow, William S. Hillyer, John Aaron Rawlins and James Simons. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/96514371/.

SOURCES

Bonekemper III, Edward H. Grant and Lee: Victorious American and Vanquished Virginian. Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, 2007.

_____. Lincoln and Grant: The Westerners Who Won the Civil War (Civil War Collection). Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, 2012. Kindle.

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Grant, Ulysses S. Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. 2 Vols. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102138632?type%5B%5D=all&lookfor%5B%5D=personal%20memoirs&ft=ft.

Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, (Military Classics). Zenith Press, 2014. Kindle.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2016. Kindle.