On This Day April 14, 2022

Washington, D.C. On April 14, 1865, U.S. president Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., at approximately 10:15 p.m. Booth shot Lincoln at point-blank range in the head from behind while Lincoln, the First Lady, and another couple were watching a play.

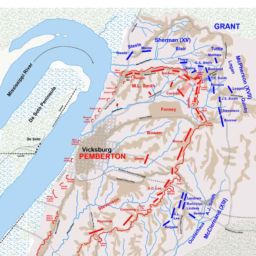

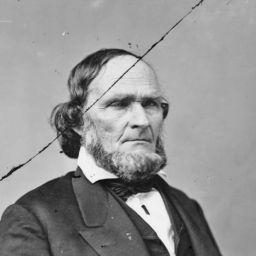

The Civil War had effectively ended just five days before, April 9, when Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to U.S. general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had been in Washington on April 14, 1865, and spoke with President Lincoln, who invited Grant and Grant’s wife Julia to accompany him and First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln that evening to see Laura Keene in Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre. Grant received a message from his wife saying that she wanted Grant, herself, and their son Jesse to leave the capital for the Grants’ cottage in Burlington, New Jersey. Grant conveyed his regrets to Lincoln.

Grant, Julia, and son Jesse took a train out of town early that evening. In route to Burlington, the news reached them that Lincoln had been shot, the wound would be fatal, and that Secretary of State William Seward had also been stabbed repeatedly by an attacker at his home—thus, a profoundly dangerous plot was unfolding.

In the subsequent hours, it would come to light that the conspirators, led by actor John Wilkes Booth, had intended to kill Lincoln, Grant, Seward, and Vice President Andrew Johnson. Remarkably, Seward survived the assassination attempt against him. President Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m., April 15, 1865.

Though inconclusive, some evidence suggests that an assassin got onto the Grant’s train. Definitely someone tried to barge into their train car, but the conductor had locked the door earlier.

What is more, as the Grants rode in a carriage towards the train station to leave Washington, D.C., John Wilkes Booth had galloped past them, though they did not of course know who he was or his designs.

As Julia related in her memoirs, a man “at a sweeping gallop on a dark horse” rode past their carriage, glaring at General Grant, then turned his horse around and rode back past them, again glaring at Grant. Then, as Jesse recorded later, the rider “wheeled his horse and rode furiously away.”

Booth had been speaking roadside with fellow actor John Mathews when the Grants’ carriage passed by. He saw it and set off on horseback in pursuit. Though we cannot know for sure that Booth was aware that the Grants were heading for the train station, historians point out that the extensive baggage on the carriage would likely have been an obvious sign to Booth.

A few days after Lincoln’s assassination, Grant related, “I received an anonymous letter from a man, saying he had been detailed to kill me, that he rode on my train as far as Havre de Grace, and as my car was locked he could not get in. He thanked God he had failed.” The letter was unsigned and we will likely never know if its contents were true.

Principal source: Ron Chernow, Grant (New York: Penguin Books, 2017), Kindle version.

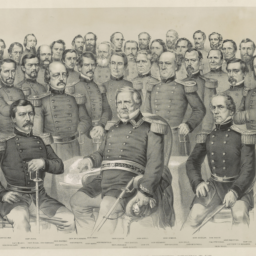

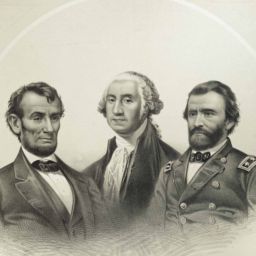

Image: The Peacemakers, George P.A. Healy (1813–1894), 1846, oil on canvas, 119.7 cm × 159.1 cm (47 1⁄8 in × 62 in), White House, Washington D.C., https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/treasures-of-the-white-house-the-peacemakers; depiction of Lincoln meeting aboard River Queen during his visit to the headquarters of general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant, March 27–28, 1865. Left to right:

Major General William T. Sherman, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, President Abraham Lincoln, and Rear Admiral David D. Porter.