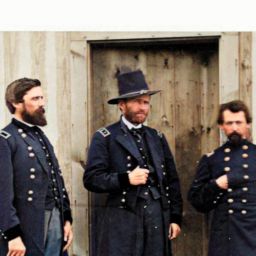

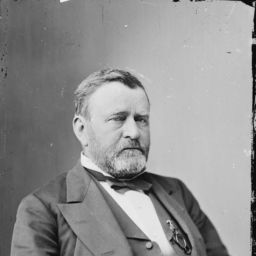

In the summer of 1864, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant felt maddeningly inert facing the entrenched Confederate lines outside of Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia.

Brooks D. Simpson, Ph.D., in his readable, authoritative, and important Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, writes:

Back on July 4[, 1864,] a soldier had scribbled in his notebook a remark attributed to Grant: “He says he could take Petersburgh (sic) and Richmond at any time but he would have to lose a great many men, and that he can take it a great deal easier by laying still and watching them.” But Grant was never much for “laying still” for long, and a siege would look like a stalemate in the eyes of the Northern electorate. He began to probe for weak spots in Lee’s lines, the idea of a full-scale assault preceded by elaborate preparation never far from his mind. If he could not change his commanders, at least he would make sure that they did their jobs. If he failed to penetrate the enemy trenches, Grant would have to swing around Lee’s right yet again to sever his rail connections to the south and west. (433)

At the same time, Grant “realized that in the North the prevailing impression of Union arms was one of failure, defeat, and stalemate” (Simpson 434). This was especially problematic given how much was at stake in the November 1864 election, only about three months away. In question was the continuation of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency and the Union war effort. The Democratic Party instead was calling for a negotiated settlement with the Confederacy.

Then came news that the advance on Atlanta, Georgia, of the U.S. armies commanded by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had stalled. This depressed the North’s mood further.

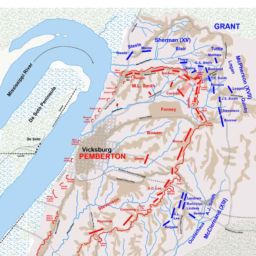

Thus, Grant seemed ready to submit to the decidedly unusual plan of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Everett Burnside, commander of the IX Corps, to try to literally blow an opening in the Confederate lines. He proposed digging a mine under a point in enemy’s lines, filling it with explosives, detonating it, and rushing U.S. troops forward into the breach.

As Professor Simpson summarizes: “What happened next was a tribute to the inability of the generals of the Army of the Potomac to set aside personal differences and to pull together to achieve a common goal (435).

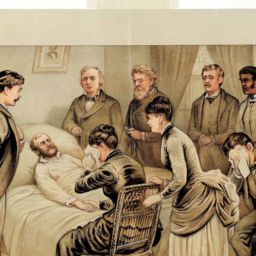

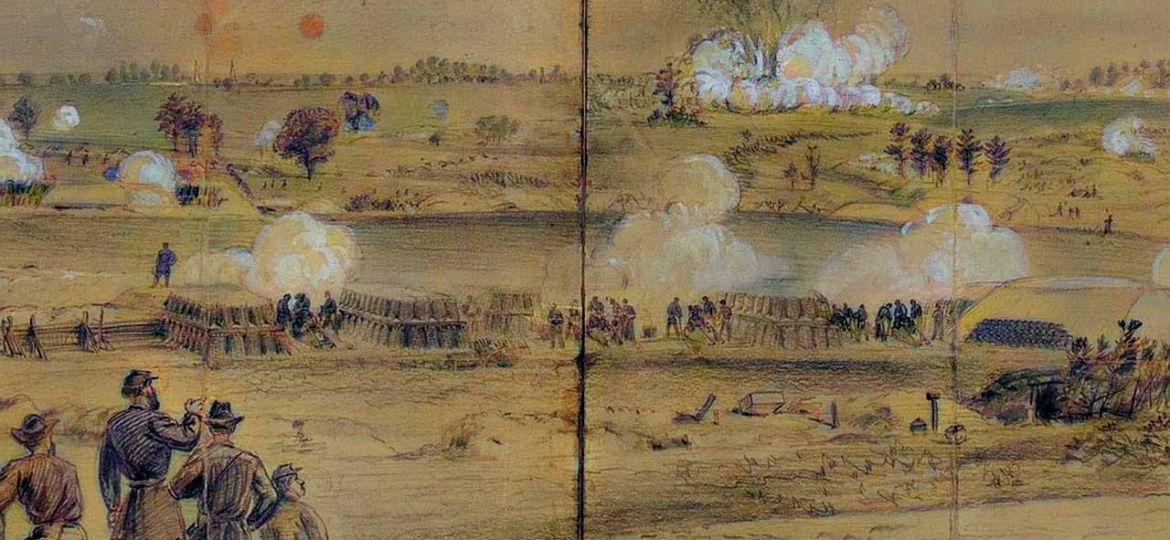

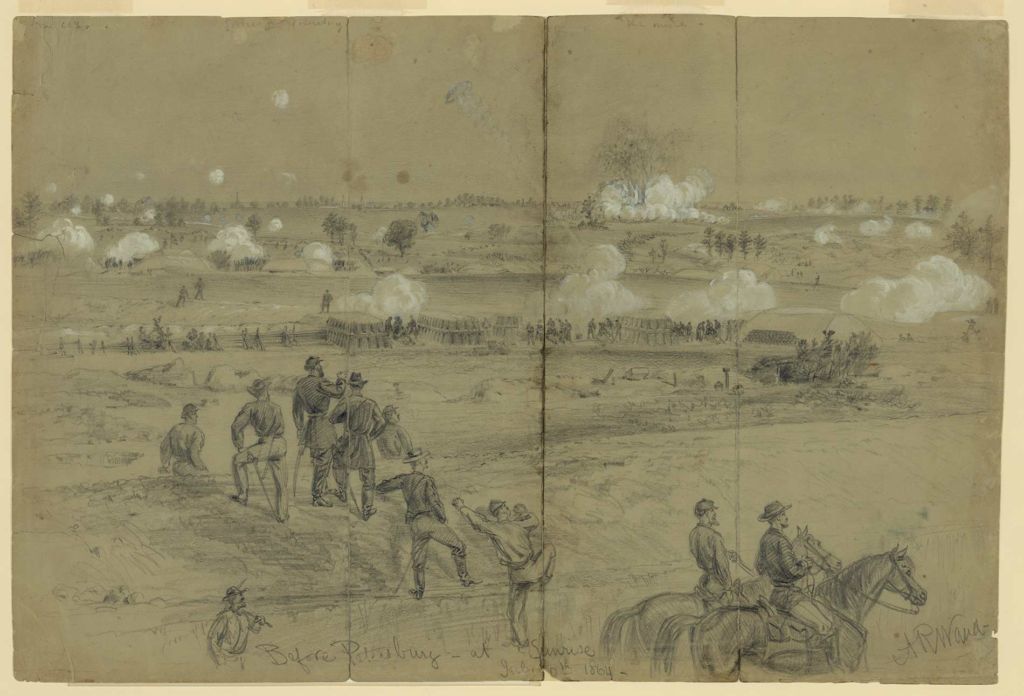

On July 30, the mine was detonated and the attack commenced. In the words of Grant himself in his Personal Memoirs, “The effort was a stupendous failure.”

I . . . expected that when the mine was exploded the troops to the right and left would flee in all directions, and that our troops, if they moved promptly, could get in and strengthen themselves before the enemy had come to a realization of the true situation. It was just as I expected it would be. We could see the men running without any apparent object except to get away. It was half an hour before musketry firing, to amount to anything, was opened upon our men in the crater. It was an hour before the enemy got artillery up to play upon them; and it was nine o’clock before Lee got up reinforcements from his right to join in expelling our troops. . . . It cost us about four thousand men, mostly, however, captured; and all due to inefficiency on the part of the corps commander and the incompetency of the division commander who was sent to lead the assault. (315)

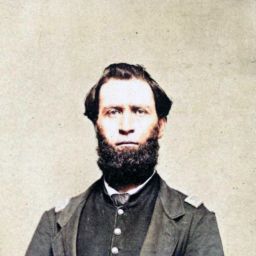

Before the attack, Gen. Burnside had resorted to having his divisional commanders draw straws to see who would lead the attack. The short straw was drawn by Brig. Gen. James Hewett Ledlie, who had been elevated from brigade to First Division command that June, and was “a poor excuse for a major general but a great drinker” (Simpson 437).

The detonation occurred at 4:46 a.m. Ledlie’s lead brigade in their advance had to first scramble over a parapet that no one had thought to remove ahead of time to quick their assault. The men “then headed, not along the sides of the crater, where they could either get through to the other side or begin rolling back the enemy flanks, but into the crater itself. Other brigades followed, and before long the massive hole in the earth was filled with thousands of soldiers, struggling to get out. As Ledlie drank in a rear area, his men botched their attack, and before long the rest of Burnside’s command succeeded in arriving just in time to be part of the repulse” (Simpson 437).

Two weeks later, Burnside took a leave of absence from the army and never returned. Clearly, Grant made a mistake in allowing Generals George Meade and Burnside, who had never worked well together, to plan and supervise the attack instead of himself.

Nonetheless, in Prof. Simpson’s assessment, Grant: “had learned something. He concluded that ‘fortifications come near holding themselves without troops.’ From now on Grant would work against both ends of Lee’s line, looking for an opportunity to outflank him, overextend him, or sever supply lines” (442).

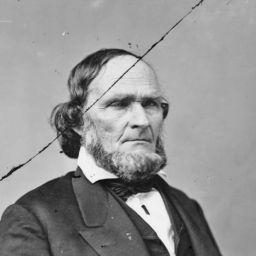

As many learners of Civil War history know, Gen. Burnside was a very problematic commander. A political appointee who had never been a professional soldier, as was the case with numerous Union and Confederate generals, Burnside made numerous mistakes in his military career.

Yet, as noted by Bruce Catton—Pulitzer Prize-winning writer of numerous popular histories related to the Civil War—in his 1951 Mr. Lincoln’s Army:, Burnside “was a simple, honest, loyal soldier, doing his best even if that best was not very good, never scheming or conniving or backbiting. Also, he was modest; in an army many of whose generals were insufferable prima donnas, Burnside never mistook himself for Napoleon” (256–257).

(The word sideburns derives from Burnside’s name. In the same passage cited above, Catton also noted: “Physically [Burnside] was impressive: tall, just a little stout, wearing what was probably the most artistic and awe-inspiring set of whiskers in all that bewhiskered Army.”)

IMAGE

Waud, Alfred Rudolph (1828–1891), July 30, 1864. Pencil and Chinese white (white watercolor of zinc oxide). 34.5 x 51.3 cm. Harper’s Weekly, August 20, 1864, 536–537. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660459/.

SOURCES

Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. Vol. 2. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102138632?

Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, (Military Classics). Zenith Press, 2014. Kindle.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Ambrose Burnside,” last modified June 9, 2022, 1:25, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambrose_Burnside.