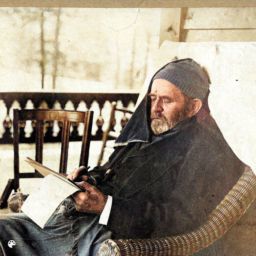

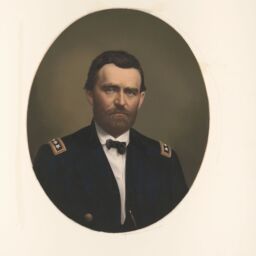

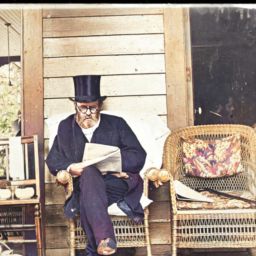

Ulysses S. Grant died at approximately 8:06 a.m., July 23, 1885.

The 18th U.S. president and former general-in-chief of the U.S. Army died in a cottage loaned to the Grants, by friend and businessman Joseph W. Drexel, as a place of refuge from New York City’s dust and heat, on Mount McGregor, in Saratoga County, New York, where amid the final stage of his terminal throat cancer, Grant could finish his memoirs.

James Harrison Kennedy describes the death of U.S. Grant in his 1888 book, The American Nation:

The end came on July 23, 1885, at six minutes after eight o’clock in the morning. He had not spoken, even in a whisper, after three o’clock in the morning “It was about four o’clock when the rattle in the throat began,” to borrow the words of one who was present at the scene.” For an hour or longer Dr. [Henry Berton] Shrady, in the hope of easing rather than of sustaining the general, as he was past that, had been giving hypodermics of brandy with great frequency. It was soon evident that the general was too far gone to be aided by stimulants. Then came the waiting for death. The general lay on the bed, his face leaden, yet with some warmth left in its hue. His eyes were closed. Power to open them had been restored to him, and it was occasionally invoked when some member of the family or the doctor or one of the attendants spoke to him. Then he would open his eyes. He could make no other recognition, but that of the eyes was clear. All eyes were intent on the general. His breathing had become soft, though quick. A shade of pallor crept slowly but perceptibly over his features. His bared throat quivered with the quickened breath. The outer air, gently moving, swayed the curtains at an east window. Into the crevice crept a white ray from the sun. It reached across the room and lighted a picture of Lincoln over the death-bed. A group of watchers in a shaded room, with only this quivering shaft of pure light, the gaze of all turned on the pillowed occupant of the bed, all knowing that the end had come, and thankful, knowing it, that no sign of pain attended it—this was the simple setting of the scene.

The general made no motion. Only the fluttering throat, white as his sick robe, showed that life remained. The face was one of peace. . . . The light on the portrait of Lincoln was slowly sinking. Presently the general opened his eyes and glanced about him, looking into the faces of all. The glance lingered as it met the tender gaze of his wife. A startled, wavering motion at the throat, a few quiet gasps, a sigh, and the appearance of dropping into gentle sleep followed. The eyes of affection were still upon him. He lay without a motion. At that instant the window curtain swayed back in place, shutting out the sunbeam. “At last,” said Dr. Shrady in a whisper.

Nothing came from the general before death which could be called his dying words. . . . There had been prayers at midnight when it was supposed he was going. Mrs. Grant then pressed his hand, and asked if he knew her. He replied with a look of re-assurance. He was near collapse at the time, and Colonel [Frederick] Grant, [U.S. Grant’s eldest son,] thinking him possibly in distress, asked him if he suffered. He whispered a feeble “no.” The question was asked several times with the same result. Once, about three o’clock, he seemed in need of something. The nurse bent over him and heard him say “water.” He did not speak after that. At different times through the night up to that hour he made himself understood by some sort of a response to questions bearing on his comfort. His last voluntary and irresponsive act of speech which embodied the idea that governed him in all his sufferings, and which will on that account stand probably as his last utterance, dates back to the afternoon before his death, when, noticing the grief that the family could not restrain, he said, whispering in a little above a breath, but yet quite distinct, “I don’t want anybody to feel distressed on my account.” There never was a more thoughtful or uncomplaining sufferer laid upon a bed of pain, nor one who showed a nobler courage or patience from the beginning to the end of months of continual suffering. (1027–1028)

IMAGES

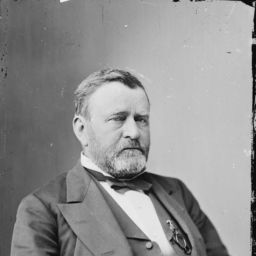

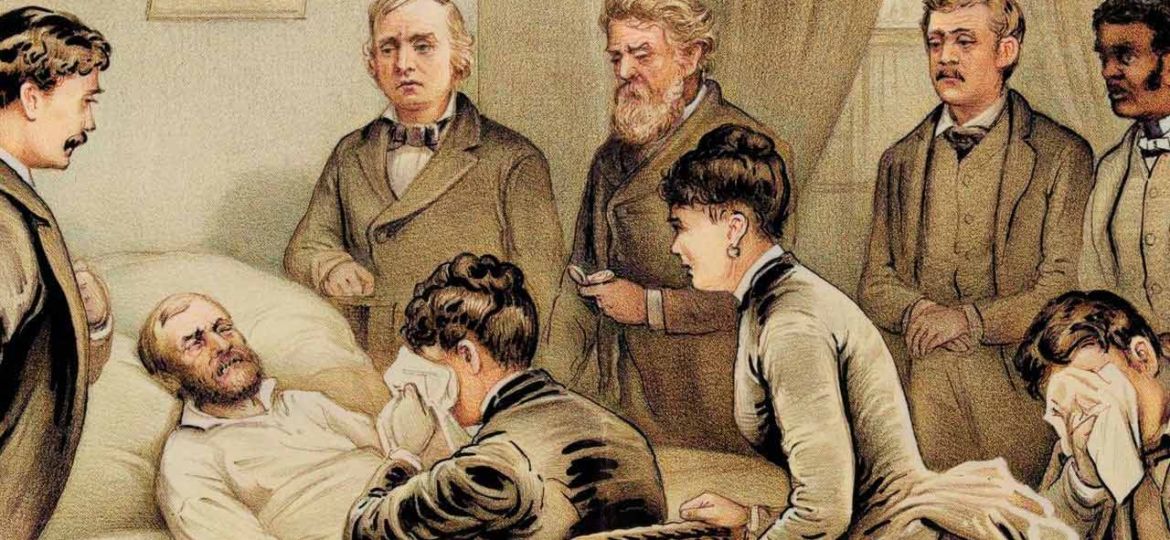

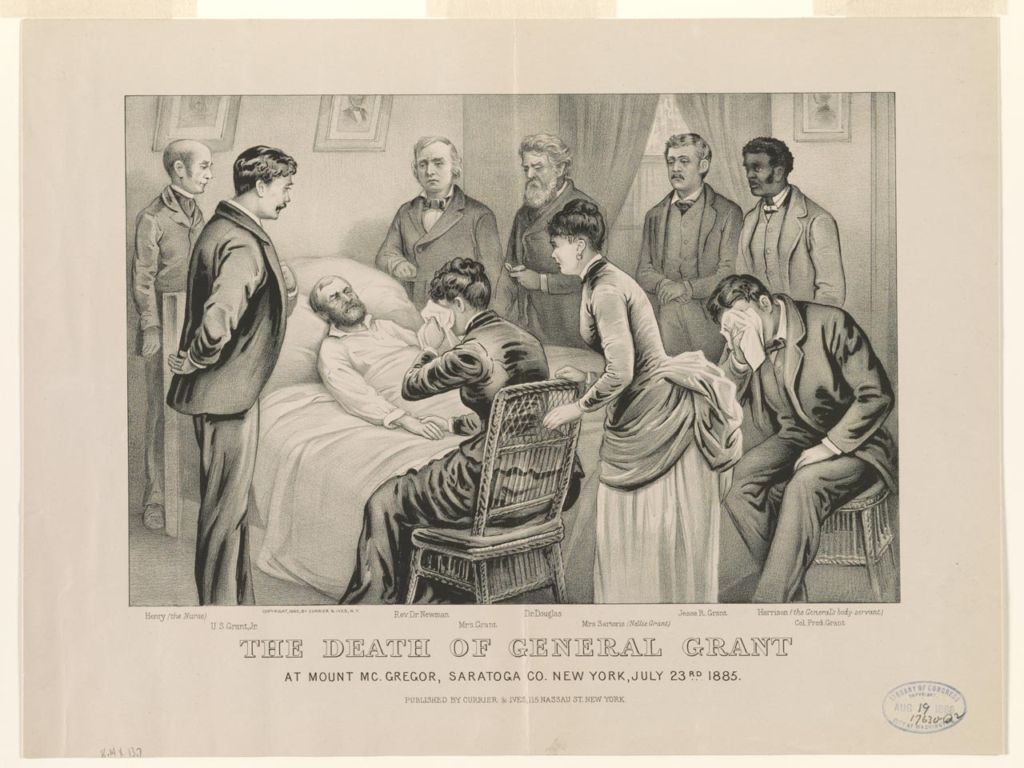

N. Currier. The Death of General Grant: At Mount Mc.Gregor, Saratoga Co. New York, July 23rd 1885, 1885. Lithograph. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/91793591/.

Those depitcted besides Grant himself are, l to r: Henry McSweeny, his nurse (McQeeney or McSweeney in some sources); Ulysses S. “Buck” Grant, Jr., Grant’s second child; Rev. Dr. John Philip Newman; Mrs. Julia Grant; Dr. John Hancock Douglas; Ellen “Nellie” Sartoris (née Grant), Grant’s third child and only daughter; Jesse Root Grant II, Grant’s fourth and youngest child; Harrison Terrell (Grant’s servant), Frederick “Fred” Dent Grant, Grant’s eldest child.

SOURCES

Benson J. Lossing [and others]. The American Nation: Its Executive, Legislative, Political, Financial, Judicial and Industrial History : Embracing Sketches of the Lives of Its Chief Magistrates, Its Eminent Statesmen, Financiers, Soldiers and Jurists, with Monographs on Subjects of Peculiar Historical Interest. Vol. 2. Edited by James Harrison Kennedy. Cleveland: Williams Publishing Company, 1888. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Nation/X7dYAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.