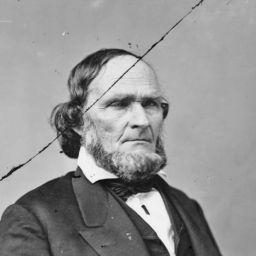

New York City & Mount McGregor, NY. It was 1885, and 63-year-old Ulysses S. Grant, former commanding-general of the U.S. Army and president of the United States, was broke, dying of cancer, and racing to finish his memoirs before Death finished him.

THE DYING WRITER

You might say Grant was writing more than a full-time writer. The year before, Grant had lost all his wealth in a Wall Street swindle. Presidents received no pension then (and wouldn’t until 1958). So, Grant hoped that proceeds from the sales of his memoirs might save his wife Julia from a widowhood of impoverishment. There was no other imaginable source of income. He had been working on the project since the summer of 1884, when the cancer started, too. At the same time, increasingly Grant’s throat cancer robbed him of speech; thus, increasingly he resorted to handwritten notes to convey his thoughts and needs to his family and physicians.

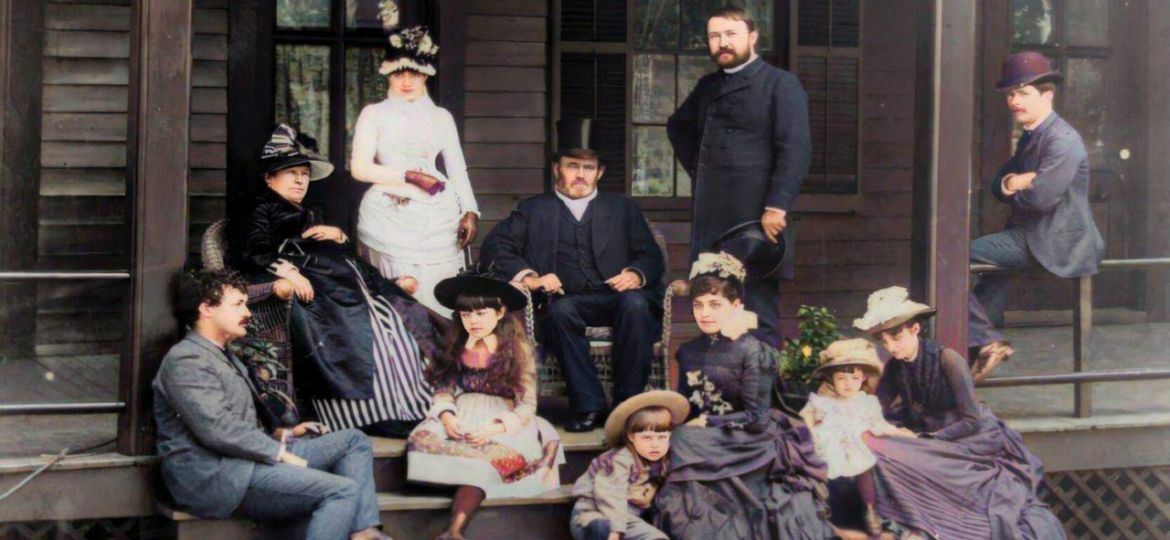

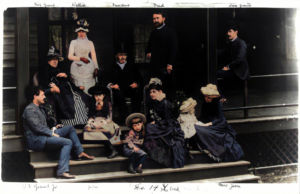

As the Grant Cottage website states, Grant pursued writing his memoirs with “the love and support of his family” and “his publisher Mark Twain” but also of “the nation at large.”

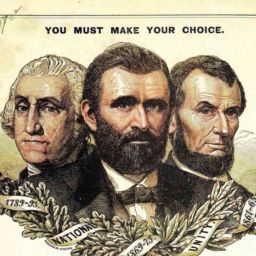

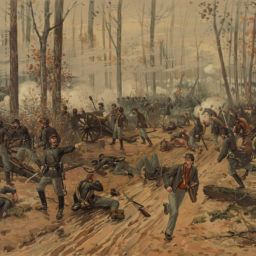

Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant would be primarily a military memoir, covering Grant’s time as victorious commanding general of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War, when North and South fought over the issues of the national union and slavery. Grant does not but in passing mention that he was for eight years the executive of the United States. And it offers no hint of his presidential administration’s efforts in defense of America’s fraught new experiment in becoming the modern world’s first biracial democracy.

De Capo Press, publisher of Charles Bracelen Flood’s Grant’s Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant’s Heroic Last Year (2011), notes that:

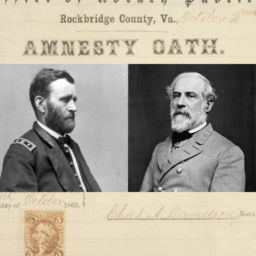

As Grant continued his work [on his memoirs], suffering increasing pain, the American public became aware of this race between Grant’s writing and his fatal illness. Twenty years after his respectful and magnanimous demeanor toward Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, people in both the North and the South came to know Grant as the brave, honest man he was, now using his famous determination in this final effort.

LEAVING NEW YORK CITY BEHIND, THE FINAL TIME

Ron Chernow in his biography Grant describes what came next:

In mid-May [1885], when Grant’s physicians wondered how to spare [Grant] the fierce heat of a Manhattan summer, his friend Joseph W. Drexel made an offer he could not resist. . . . Drexel was a minor partner in the Hotel Balmoral, recently opened at the peak of Mount McGregor, 1,100 feet above sea level [in Upstate New York]; just down the road he had built a charming, roomy cottage that he placed at Grant’s disposal.

. . . .

The doctors loved the idea of Grant breathing in pine-scented mountain air, free from summer heat, mosquitoes, and noxious city vapors. . . . After Grant suffered a bad day [at his Manhattan townhouse] and postponing the trip was reluctantly broached to him, he exclaimed, “Now or never!” (948)

And so, on June 16, 1885, for the second time in his life, Ulysses S. Grant made an escape from New York City.

He had done so in 1854. Homesickness and boredom had beset him on an army base in California. He’d not seen his family for four years. Grant took to drinking to cope, and Grant could never drink just a little, it seems, when he dared to do so. Facing a possible court martial due to his behavior, Grant gave up on an army career and sought to return to his wife Julia his two children—Frederick (“Fred”) and Ulysses, Jr. (“Buck”)—then living at Julia’s family’s plantation outside of St. Louis, Missouri (Chernow 85). He went the quickly way possible in those days: not traversing the Rocky Mountains and America’s vast plains, but going by ship to Central America, trekking overland to the Atlantic coast, then taking another ship to New York. Stranded in Gotham, since Grant hadn’t a penny to his name, his brother came at their father’s instruction to collect him (Chernow 91).

DEPARTURE WITH FAMILY & HARRISON TERRELL

Grant’s second departure differed significantly. Ronald C. White, Jr. describes the scene in American Ulysses.

On the morning of June 16, crowds gathered to witness Grant’s departure. At Grand Central Terminal, he boarded a special train provided by William Vanderbilt. Although it was a sultry summer day, Grant dressed in a long Prince Albert coat with a white silk scarf enveloping his neck. (646)

Among those accompanying Grant were physician John Douglas, Grant’s son Fred, Grant’s wife, Mrs. Julia Grant, and the ever-present William Henry Harrison Terrell, who went by Harrison. A former slave, Terrell had been a paid servant among the Grants’ small household staff. When the Grants went broke and could no longer pay wages, Terrell stayed anyway, determined to help (Trimm 19). Grant on June 2, 1885, had penned to Terrell a letter of reference and gratitude:

I give this letter to you now, not knowing what the near future may bring to a person in my condition of health. This is an acknowledgement of your faithful services to me during my sickness up to this time, and which I expect will continue to the end. This is also to state further that for about four years you have lived with me, coming first as a butler, in which capacity you served until my illness became so serious as to require the constant attention of a nurse, and that in both capacities I have had abundant reason to be satisfied with your attention, integrity and efficiency. I hope that you may never want for a place. Yours, U.S. Grant

(Trimm 27)

DREXEL’S COTTAGE, MOUNT MCGREGOR—HAVEN & HOSPICE

The train journey up the Hudson Valley took about five hours. White:

In the afternoon, a tired Grant arrived at [the] cottage. He liked the expansive open porch that surrounded the house on three sides. The scent of the Adirondack Mountains’ northern pines pleased him. As the nighttime temperature fell into the fifties, Grant was able to sleep for the first time in days. [Grant’s cancer prevented him from sleeping laying down; he slept propped up in a leather chair. – ed.] (White 646)

By this point, Grant could barely speak and asked for his writing materials since he could no longer dictate. . . . Once he began to write about the Virginia Campaign, the pace of the narrative slowed down. By now his cursive writing, always so strong and clear, had begun to decline. He wrote [to] Douglas, “I can feel plainly that my system is preparing for dissolution.” Douglas . . . believed only Grant’s commitment to finishing his memoirs was keeping him alive (White 647).

Both that Herculean writing effort and Grant’s life would end at that two-story, wooden cottage. During Grant’s 36 days at the cottage, many people passed by, especially given the cottage’s proximity to the hotel, which provided daily meals to the cottage’s occupants. (Grant himself could barely eat.)

Louis Picone in his remarkable book, Grant’s Tomb: The Epic Death of Ulysses S. Grant and the Making of an American Pantheon, describes this aspect of the Grants’ time there:

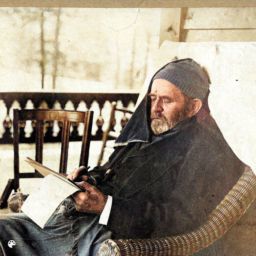

Many people also traveled to the cottage to see Grant, understanding it might be his final stand. An elderly Union veteran, Sam W. Willett, volunteered to keep the visitors from bothering Grant and set up a small white tent outside the home to keep guard. Some who traveled to the cottage were soldiers hoping to see their former commander one last time; more than a few were peddlers and medicine salesmen trying to gain entrance to the home and sell their wares; many were tourists, lured by Drexel’s advertising. One newspaper reported, “Placards and handbills have been widely distributed in Saratoga and elsewhere announcing excursions . . . containing the big-type name of Grant to catch the eye.” The visitors slowly walked past the home in hopes of a glimpse of Grant on the porch, where he often sat wearing a wool cap with a blanket on his lap despite the eighty-degree temperatures. Their most sought and treasured reward was a silent nod from Grant. (36)

Finally, on July 20, Grant achieved a final victory by outracing cancer and finishing his memoirs, a work of some 285,000 words written over the course of only about one year. Today, it is widely viewed as a masterpiece and likely the foremost military memoir in the English language. Posthumously published beginning in December 1885, the two-volume memoir would quickly sell 300,000 copies. No previous book had ever sold so many copies in such a short period of time. (Chernow 952–953) Julia would eventually amass more than $420,000 in royalties, about $13,000,000 today (Picone 99).

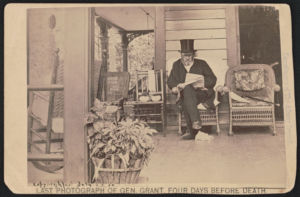

On that same milestone day, Grant “sat on the porch in a top hat and read the papers. His photograph was taken—the last one.” (Picone 40) Harrison Terrell is barely visible within the shadow of the open doorway.

Also that day, Grant undertook a final albeit short journey, as Chernow relates:

Ulysses S. Grant asked to be rolled over to a scenic spot on the mountaintop that offered a wide-angled vista of the Adirondack foothills to the north, the Green Mountains of Vermont to the east, and the Catskills dimly visible to the south. Bundled up with a blanket over his lap, he was wheeled in a bath wagon that had two large wheels in the rear, a smaller one up front, which Harrison Terrell pushed from behind with a metal bar. A few weeks earlier, Terrell had pulled Grant up to the Hotel Balmoral, facetiously complaining he had been reduced to a draft horse, to which Grant scribbled: “For a man who has been accustomed to drive fast horses this is a considerable comedown in point of speed.” But this new outing lacked humor and left Grant gasping for air. (953)

After that final outing, the end came quickly. Picone describes it:

On Wednesday, July 22, Grant spoke in a hushed whisper to his family, “I don’t want anybody to feel distressed on my account.” This was the last significant verbal statement he would ever make.

. . . . .

Grant had been lying in his chair, as he had every night for several months, but now he asked his doctors to move him to his bed.

. . . . .

At about 3:00 a.m. on July 23, the general appeared agitated and wanting. . . . Dr. Shrady could offer comfort, but nothing more, and applied hot cloths and mustard and injected Grant with brandy.

. . . . .

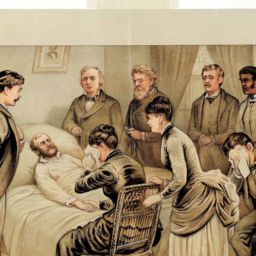

At around 7:45 a.m., Dr. Shrady summoned the family.

. . . . .

Grant opened his eyes one last time. He slowly looked around the room and saw his wife and four children surrounding the bed; his three daughters-in-law at the foot; his physicians, Doctors Douglas, Sands, and Shrady; Nurse McSweeny in the corner; and his loyal companion Harrison Tyrrell (alternatively spelled “Terrell”) by the doorway. Ulysses S. Grant closed his eyes and took his last breath. It was 8:06 a.m., Thursday, July 23, 1885. (40–42)

The death of Grant swept the nation and world. Two decades after the end of the American Civil War, amid America’s Gilded Age, the passing of the great general and former president had a unifying effect. Messages of condolences and respect were published in newspapers in both the North and South.

Chernow:

When John Singleton Mosby, [former Confederate cavalry commander of “Mosby’s Raiders,”] learned of his death, he was bereft: “I felt I had lost my best friend.” In Gainesville, Georgia, a white-bewhiskered James Longstreet, [one of the War’s foremost Confederate generals,] emerged in a dressing gown to tell a reporter emotionally that Grant “was the truest as well as the bravest man that ever lived.” In southern towns and border states, veterans from North and South linked arms as they paid tribute to Grant’s passage. Black churches held “meetings of sorrow” that eulogized Grant as a champion of the Fifteenth Amendment and the fight to dismantle the Ku Klux Klan. Summing up Grant’s career, [abolitionist, statemen, and orator] Frederick Douglass wrote: “In him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.” (956-957)

TOURING GRANT COTTAGE NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK

On Saturday, May 28, 2022, two friends and I joined a tour of the cottage. Painted as has always been the case in ginger yellow and trimmed in a vaguely rose-toned chocolate brown, the cottage is nestled in its wooded perch above the small town of Wilton.

While Grant Cottage encourages people to book their tours in advance like we did (it was Memorial Day weekend so we suspected they’d be busy), it is not required and they usually have openings for walk-ins throughout the day. Tours booked in advance are timed. We were heartened to hear that our group was the largest-yet that volunteer guide Diana had led since the pandemic! We took this to be a very encouraging sign that the cottage can enjoy an appreciable increase in the number of visitors after the pandemic had forced them to necessarily close for a while.

The cottage, which recently gained national landmark status as the Ulysses S. Grant Cottage Historical Landmark, conveys a strong sense of place and history. Its homepage explains:

Today, the cottage remains essentially the same as during the Grant family’s stay. Visitors tour the downstairs of the cottage, viewing the original furnishings, decorations, and personal items belonging to Grant, including the bed where he died, and floral arrangements that remain from Grant’s August 4th funeral [in 1885].

I can highly recommend Grant Cottage, including its visitor center and bookstore.

There are several interesting events coming up at Grant Cottage, some that you can join virtually. This Saturday, June 18, 2022, is a family-friendly U.S. Grant Bicentennial Birthday Celebration.

When you visit the cottage, be sure to leave time for the app-based audio tour of the grounds and overlook. There are explanatory markers, too. Other U.S. Grant-related historical markers nearby, and at least one of the aforementioned explanatory placards on the grounds (concerning the Hotel Balmoral) can be viewed on the Historical Marker Database (HMDB) online. On the database’s page “The Hotel and Ulysses S. Grant at Mt. McGregor,” scroll down to the “Other nearby markers” section.

A truly once-in-a-lifetime Cottage-related special event occurs on October 16, 2022: a U.S. Grant Bicentennial Gala at the nearby Gideon Putnam Resort and Spa.

Grant Cottage is only nine miles from Saratoga Springs, featuring an upmarket, historic main street with numerous restaurants, dozens of exquisitely maintained historical residential facades on both thoroughfares and side streets, some now as commercial or institutional properties, the New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, and the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame. Nearby is the National Park Service’s Saratoga National Historic Park. There in 1777, “during the American War for Independence, American troops battled and beat a British invasion force, marking the first time in world history that a British Army ever surrendered.” (NPS’s SNHP homepage)

If you heard about Grant Cottage here first and visit, please let them know you learned about the cottage from Grant Revealed.

If you’ve not done so already, consider signing up for the Ulysses S. Grant Revealed Newsletter.

SEE 8 ADDITIONAL PHOTOS FROM MAY 28, 2022, GRANT COTTAGE TOUR

Click to enlarge.

SOURCES

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Picone, Louis L. Grant’s Tomb: The Epic Death of Ulysses S. Grant and the Making of an American Pantheon. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2021. Kindle.

Rocca, Mo. “Ulysses S. Grant’s last battle.” CBS Sunday Morning. Segment article, February 17, 2013. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ulysses-s-grants-last-battle/.

Trimm, Steve. General Grant’s Supporting Players. Friends of The Ulysses S. Grant Cottage, 2019.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2016. Kindle.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Bath chair,” last modified April 13, 2022, 06:01, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bath_chair.