Washington, D.C., Grant’s peacetime generalship. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and Major General Phil Sheridan took the U.S. a step closer to invading Mexico less than three months after the American Civil War ended.

On June 30, 1865, Grant received a message from Sheridan reading in part:

Large and small bands of rebel [i.e., former Confederate] soldiers and some citizens amounting to about two thousand have crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico. Some allege with the intention of going to Sonora. ‘The Lucy Given’ a small steamer was surrendered at Matagorda but was carried off and is now anchored at Bagdad on the Rio Grande. There is no doubt in my mind that the representatives of the [French-backed] Imperial Government [in Mexico] along the Rio Grande have encouraged this wholesale plunder of property belonging to the U S Government and that it will only be given up when we go and take it. . . . Gen Steele says that the French officers are very saucy and insulting to our people at Brownsville. . . . The rebels who have gone to Mexico have their sympathies with the Imperialists and this feeling is undoubtedly reciprocated. . . . [E]ight hundred and twenty six bales of confederate states cotton stored at Rio Grande City was crossed into Mexico and this is only one item. (Papers 163–164)

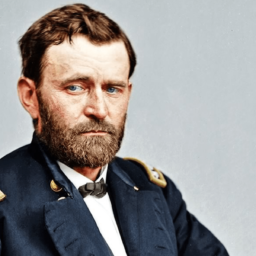

For four years after the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant remained the commanding general of the U.S. Army and its sole lieutenant general, a rank that only George Washington had held previously, until the U.S. Congress promoted Grant on July 25, 1866, to the unprecedented rank of General of the Army of the United States.

The Postbellum Generalship of Ulysses S. Grant

During his peacetime generalship, Grant’s concerns included Mexico. As Ron Chernow explains in Grant, in 1862, as the American Civil War raged, Napoleon III, Emperor of the French:

began to send an army of occupation to Mexico, under the pretext of collecting overdue debts, to topple the legitimate government of Benito Juárez and install a puppet regime under Ferdinand Maximilian, an Austrian archduke.

. . . . .

There was so much cross-border skulduggery between France and the rebels during the Civil War—the Confederacy regularly smuggled supplies across the Rio Grande while its soldiers used Mexico for sanctuary—that Grant classified Napoleon III as “an active part of the rebellion.” (554–555)

Edmund Kirby Smith’s Residual Rebellion After Appomattox

After Robert E. Lee surrendered the secessionist confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, pockets of Southern rebellion lingered.

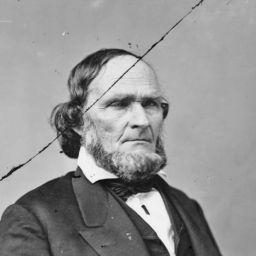

For example, Confederate general Edmund Kirby Smith still asserted control with armed men over parts of Texas and Louisiana.

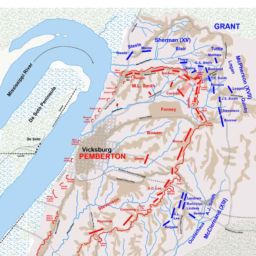

In May 1865, Grant appointed Phil Sheridan commander of the Military District of the Southwest and dispatched him with 50,000 men to compel Smith’s surrender. Smith did so on June 2, 1865.

While Sheridan continued with his oversight in the region, he alerted Grant that defeated Confederates had sacked U.S. arsenals and taken the weapons into Mexico.

As the 1865 summer wore on, in meetings of the cabinet of President Andrew Johnson, Grant continued to push possible military intervention in Mexico. In this, as Chernow rightly surmises:

Grant allowed his political judgment, which could be faulty, to supersede his military caution.

. . . . .

With Mexico Grant played a dangerous game, hoping to reunite North and South under the banner of a popular foreign war. (Chernow 555–556)

Secretary of State Seward’s Savvy Concerning Mexico

However, the remarkably adroit Secretary of State William H. Seward prudently saw that diplomacy and patience might far more effectively and easily accomplish American interests in Mexico. Seward had successfully worked during the Civil War to ensure the continued neutrality of the United Kingdom and other nations. And his perspective on the Mexico situation won the day with President Johnson the cabinet.

From April 1865 on, Grant as commanding general of the U.S. Army also had to concern himself with the tasks of mustering out— downsizing—the army now that the war had ended. He also increasingly met evidence that undermined his initial optimism regarding Southern acquiescence to federal Reconstruction policies. He saw that U.S. federal military presence in the South would need to be maintained and actively managed, especially if any hope would emerge for former slaves to viably enter into U.S. political life.

I believe that such matters as well other projects of Grant’s during his postbellum generalship not mentioned here, as well his growing disagreements with President Johnson and the political considerations that that entailed, probably diluted his commitment to Mexican intervention.

Seward proved right. Maximilian’s hold on Mexico continued to wane, his Second Mexican Empire having never been more than a client state of the Second French Empire. Maximilian’s imperial aspirations ran counter to rising liberal, republican, and anti-European sentiment in Mexico.

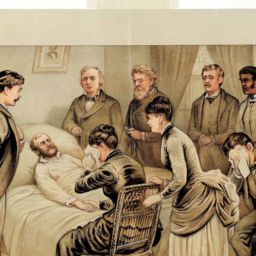

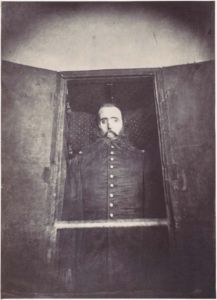

By the fall of 1865, Maximilian’s supporters were clearly on the defensive. In 1866, French forces withdrew from Mexico. It should be noted, however, that persistent threat of U.S. military intervention in Mexico, such as Grant leaned towards, factored into Napoleon III’s decision to abandon France’s Mexican adventure and appeal to Maximilian I to abdicate, which he refused to do. In 1867, Maximilian I was captured by Mexican Republican forces, and on June 19 of that year, he was executed by firing squad.

E.K. Smith and Philip Henry Sheridan

Former Confederate general Edmund Kirby Smith, whose forces remained in a certain degree of rebellion in Texas and Louisiana for a brief period after Lee surrendered, fled to Cuba initially. But he returned shortly. He took the amnesty oath of allegiance to the U.S. at Lynchburg, Virginia, on November 14, 1865. He went on to become a professor and co-chancellor of the University of Nashville.

Phil Sheridan remained a career soldier, later becoming General of the Army, the rank U.S. Grant first held. He championed the protection of what would become Yellowstone National Park and received various honors. Several counties and towns in the U.S.A. are named after him, as is Sheridan Square, often considered the symbolic heart of New York City’s storied, historic, West Village. However, Sheridan’s viciousness as a military commander against Native Americans in the late 1860s, including against the Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa, significantly stains his reputation today. Though Sheridan always denied having said it, attributed to him is the remark, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead,” which is often remembered in its misquoted form, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

Sign up for the Grant Revealed Newsletter

IMAGES

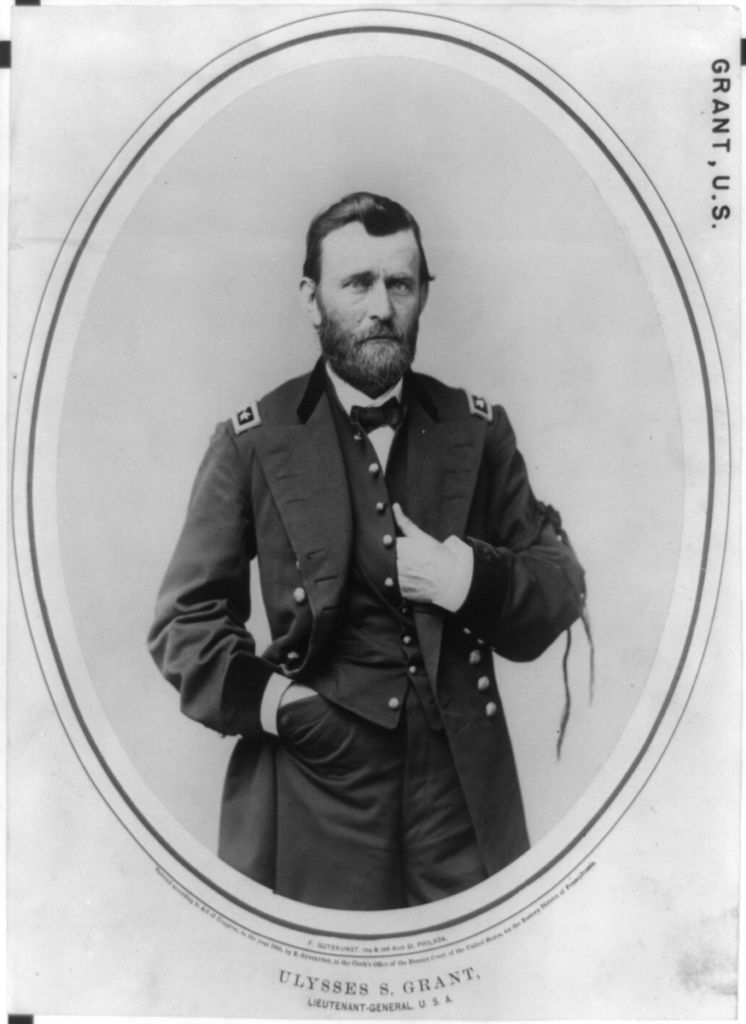

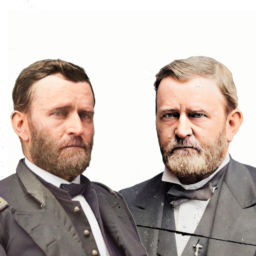

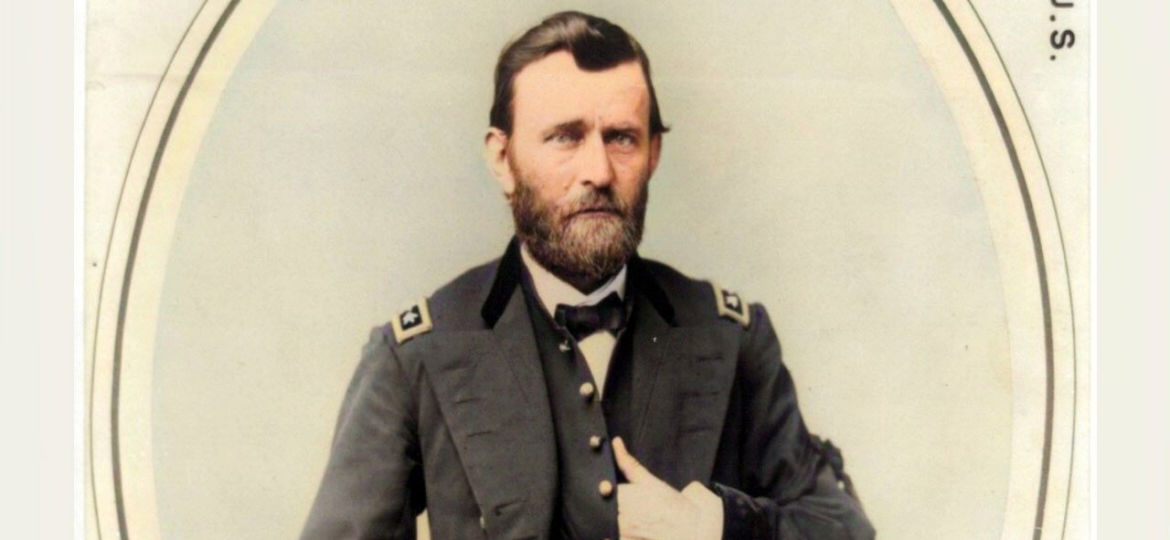

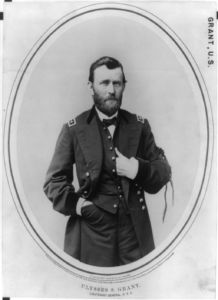

Featured (cropped, colorized), inset, and below: Gutekunst, Frederick (1831–1917). Ulysses S. Grant, Lieutenant-General, U.S.A., 1865. Albumen print. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00652563/. (Note that Lt. Gen. Grant wears a black mourning band on his left arm following the assassination of President Lincoln.)

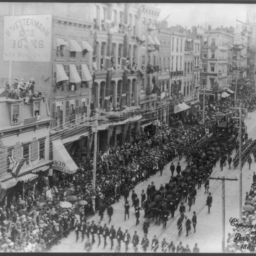

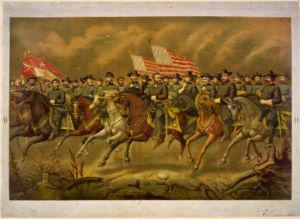

Boell, E. [Ulysses S. Grant and his Generals on horseback], 1865. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3g02081/. (Note that Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan is the officer farthest to the left whose full length including his left leg is visible.)

Aubert, François (1829–1906). [The Corpse of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico], 1867. Albumen silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/266168.

SOURCES

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Simon, John Y., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 15: May 1-December 31, 1865 (1988). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usg-volumes/22.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Edmund Kirby Smith,” last modified June 25, 2022, 19:23, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Kirby_Smith.

_____, s.v. “Philip Sheridan,” last modified June 29, 2022, 06:38, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Sheridan.