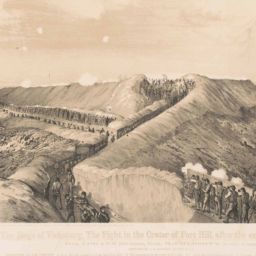

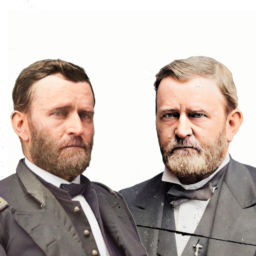

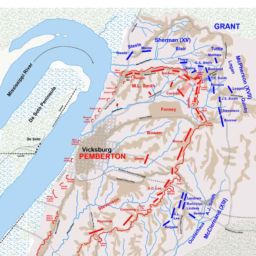

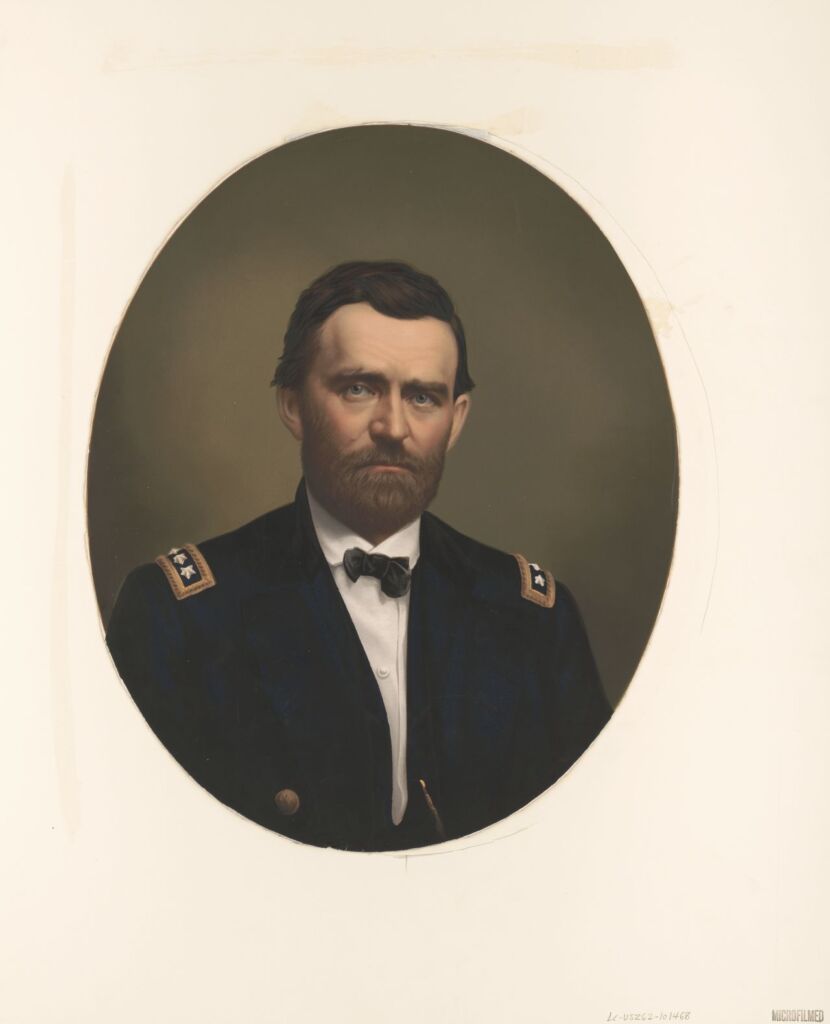

Ulysses S. Grant is of profound importance in the history of the American Civil War. From relatively early on in the war, Ulysses S. Grant won battles in the war’s western theater of operations, including the Battle of Fort Donelson (February 11–16, 1862), the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862)—though it was almost lost by the Union on its first day—and the Siege of Vicksburg (May 18, 1863–July 4, 1863).

“Unconditional Surrender” Grant

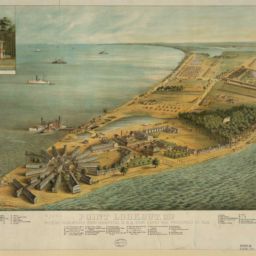

At the Battle of Fort Donelson, Grant was a brigadier general leading the roughly 25,000-man army of the District of Cairo, named after Cairo, Illinois. When it became clear that Grant’s forces attacking the Confederate army within the fort would win, the Confederate commander—who Grant knew personally from before the war—asked Grant what terms Grant would offer him if the Confederate army were to surrender. Grant replied that there were no terms, only “unconditional surrender” would be accepted. This earned Grant the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

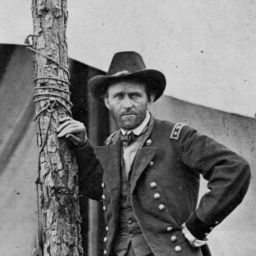

Grant rose in the ranks from colonel to major general, along the way learning from his own as well as his Union colleagues’ and Confederates’ mistakes. The war dragged on, marked by large engagements, staggeringly high combat and disease casualty rates, a continental scope, innovations in weapons and tactics, and a strengthening commitment by the Union to end slavery everywhere it could within the U.S.A., once and for all.

The whole world watched to see if the United States would survive or if the world’s first modern, Constitutional democratic republic would succumb to self-destruction.

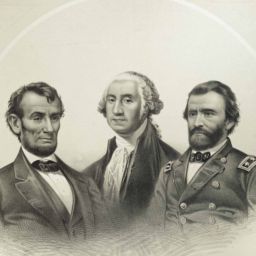

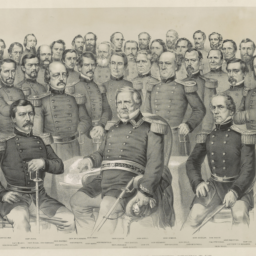

In 1864, after Grant’s various victories, President Abraham Lincoln called Grant to the war’s Eastern Theater, placing him in overall command of all Union forces, and charged him with the task of leading the Union to final victory—though all previous generals Lincoln had appointed to that task had failed to do so.

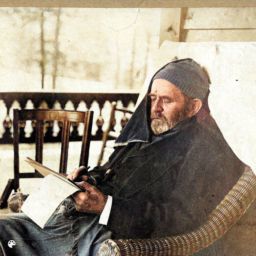

Grant was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, the first American to hold that rank since George Washington nearly 100 years before. As a lieutenant general, Grant successfully ended the Civil War by defeating the army of Confederate general Robert E. Lee after the two men’s armies endured months of battles, strategic infantry and cavalry maneuvers, and siege warfare. Lee surrendered to Grant at the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. The war effectively ended at that point. At great cost, the American republic had been preserved—hopefully to endure—and the path was secured towards the de jure and complete emancipation of slaves and abolition of slavery in the United States.

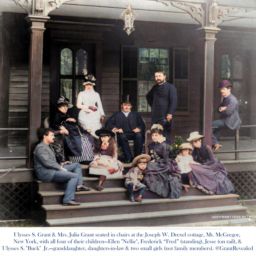

Grant gave generous terms of surrender to Lee—rightly seeing his former enemies as fellow countrymen—allowing Confederate officers to keep their sidearms, private horses, and baggage, and allowing many other soldiers to keep their private horses that had been in use by Confederate cavalry and artillery units. Grant also supplied the men of Lee’s army with rations. Lee said that Grant’s actions would “be very gratifying and will do much toward conciliating our people.” (Baier 148)

Grant’s gestures at Appomattox Court House promoted the spirit of reconciliation and reunification following the civil war, which cost between 620,000 and 750,000 American lives in total, on both sides of the conflict, and $5 billion dollars. (At least $100 billion in today’s value.) (Baier 159)

Also during the war, Grant provided food, work opportunities, medical care, and education to thousands of self-liberated former slaves who reached his armies, months before Abraham Lincoln issued the official Emancipation Proclamation that declared that slaves in the South under Confederate control would now be deemed free by the U.S. government upon the arrival of Union troops. (Douglass)

Bret Baier, Catherine Whitney, To Rescue the Republic (HarperCollins, 2021). Kindle.

Frederick Douglass, U.S. Grant and the colored people. (Washington, D.C.: Union Republican Congressional Committee, 1872).

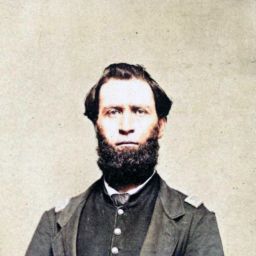

[Major General Ulysses S. Grant]. Cincinnati, O[hio] : Published by E.C. Middleton & Co., Cincinnati, O., [1866?]. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/90712173/