FAQs — Frequently Asked Questions About Ulysses S. Grant

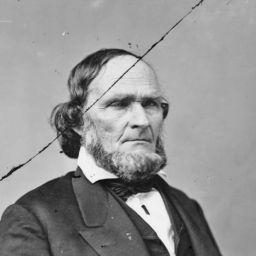

Grant was both the victorious commanding general of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865) and a two-term president of the United States (1869–1877).

He was born in 1822 in Ohio. His family named him Hiram Ulysses Grant. He died in 1885 in Upstate New York.

For much of his life after 1865, he was quite likely the most famous living American in the world.

Nearly 1.5 million people came to the streets of New York City to witness his funeral procession on August 8, 1885, the largest public gathering in American history up to that time.

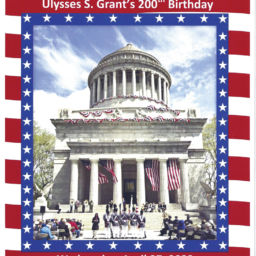

Until after World War I, his tomb, the General Grant National Memorial, in New York City’s Riverside Park, received more annual visitors than the Statue of Liberty.

Ulysses S. Grant was important as the highest-ranking commander in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War and as the 18th president of the United States. He was the youngest U.S. president ever elected (age 46 in 1868) until John F. Kennedy (age 43 in 1960).

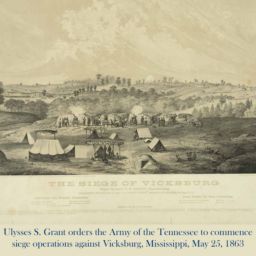

Grant’s military campaigns during the Civil War, especially his campaign to capture the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, are still studied in military academies today.

While president, the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified, guaranteeing the right to vote for all adult American men including former slaves (freedmen). Also, the Enforcement Act (or Civil Rights Act or “Ku Klux Klan Act”) of 1871 was passed at Grant’s insistence. It allowed him to use the U.S. military, the new Department of Justice, and federal judges to combat intimidation and violence against Blacks in the South.

The American Civil War was a bloody contest that pitted America’s majority Northern and border states loyal to the American republic and its federal government (collectively “the Union”) against secessionist Southern states (“the Confederacy”) primarily over the issue of the expansion of race-based, chattel slavery into new U.S. territories and states, though sectional divisions—political, economic, and cultural—and Constitutional issues also contributed to the war’s outbreak.

For many years before the Civil War, the antebellum period in America, the expansion of legal slavery into new U.S. territories and states was hotly debated across the nation—from dining room tables to the U.S. Congress’s chambers. Many of the new U.S. territories and states emerging at the time were carved from of a massive expanse of land that the U.S. acquired through victory in the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), in which Ulysses S. Grant fought with distinction as a lieutenant despite the fact that he was primarily absorbed with quartermaster duties.

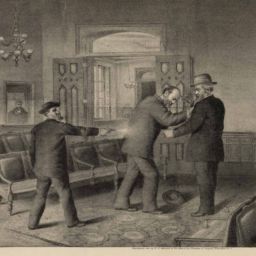

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln won the U.S. presidential election as the candidate of the nascent Republican Party, which opposed slavery’s expansion into any new U.S. territories or states. By that time, 18 states had outlawed slavery. But 15 had not. In response to Lincoln’s electoral win, 11 pro-slavery states of the South began an armed secessionist movement. As a putative new nation, the Confederate States of America (C.S.A.), these states asserted complete independence from the United States of America (U.S.A.). The remaining majority of America’s populace, in the states of the North and border states, led by President Lincoln and the federal government, set out to preserve the republic’s union of states and inalterably diminish the role of slavery in it. As the war progressed, an increasing number of Union supporters considered, as some had from the start, the emancipation of slaves and the total abolition of slavery as vital goals and part of the moral bedrock of their cause.

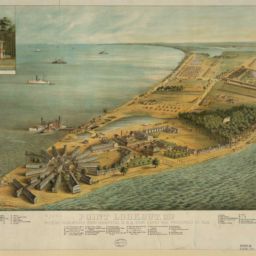

From relatively early on in the American Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant won battles in the war’s western theater of operations, including the Battle of Fort Donelson (February 11–16, 1862), the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862)—though it was almost lost by the Union on its first day—and the Siege of Vicksburg (May 18, 1863–July 4, 1863).

At the Battle of Fort Donelson, Grant was a brigadier general leading the roughly 25,000-man army of the District of Cairo, named after Cairo, Illinois. When it became clear that Grant’s forces attacking the Confederate army within the fort would win, the Confederate commander—who Grant knew personally from before the war—asked Grant what terms Grant would offer him if the Confederate army were to surrender. Grant replied that there were no terms, only “unconditional surrender” would be accepted. This earned Grant the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

Grant rose in the ranks from colonel to major general, along the way learning from his own as well as his colleagues’ and Confederates’ mistakes. The war dragged on, marked by large engagements, staggeringly high combat and disease casualty rates, a continental scope, innovations in weapons and tactics, and a strengthening commitment by the Union to end slavery everywhere it could within the U.S.A., once and for all.

The whole world watched to see if the United States would survive or if the world’s first modern, Constitutional democratic republic would succumb to self-destruction.

In 1864, after Grant’s various victories, President Abraham Lincoln called Grant to the war’s Eastern Theater, placing him in overall command of all Union forces, and charged him with the task of leading the Union to final victory—though all previous generals Lincoln had appointed to that task had failed to do so.

Grant was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, the first American to hold that rank since George Washington nearly 100 years before. As a lieutenant general, Grant successfully ended the Civil War by defeating the army of Confederate general Robert E. Lee after the two men’s armies endured months of battles, strategic infantry and cavalry maneuvers, and siege warfare. Lee surrendered to Grant at the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. The war effectively ended at that point. At great cost, the American republic had been preserved—hopefully to endure—and the path was secured towards the de jure and complete emancipation of slaves and abolition of slavery in the United States.

Grant gave generous terms of surrender to Lee—rightly seeing his former enemies as fellow countrymen—allowing Confederate officers to keep their sidearms, private horses, and baggage, and allowing many other soldiers to keep their private horses that had been in use by Confederate cavalry and artillery units. Grant also supplied the men of Lee’s army with rations. Lee said that Grant’s actions would “be very gratifying and will do much toward conciliating our people.”1

Grant’s gestures at Appomattox Court House promoted the spirit of reconciliation and reunification following the civil war, which cost between 620,000 and 750,000 American lives in total, on both sides of the conflict, and $5 billion dollars. (At least $100 billion in today’s value.)2

Also during the war, Grant provided food, work opportunities, medical care, and education to thousands of self-liberated Black former slaves who reached his armies, months before Abraham Lincoln issued the official Emancipation Proclamation that declared that slaves in the South under Confederate control would now be deemed free by the U.S. government upon the arrival of Union troops.3

Throughout the war, Ulysses S. Grant carried out military offensives with uncommon determination. Also, drawing on his earlier experiences as a quartermaster in the U.S. Army before he had field commands, he integrated logistics and combat operations with uncommon skill. He showed remarkable cool-headedness during battle, too.

President Grant served as 18th president of the United States (1869–1877), winning the presidential elections of 1868 and 1872 as the Republican Party’s candidate.

As U.S. President, Grant strove to protect the millions of Blacks in the South, who had been recently freed from chattel slavery, against violence and intimidation from militant opponents of Reconstruction (1865–1877). Reconstruction was the federal government-led effort to reintegrate the 11 Southern states of the Confederacy back into American governance and to newly integrate the country’s approximately 4,000,000 former slaves into the nation’s political structures, paid-labor economy, and civil society.4

During Grant’s presidency, African Americans made impressive political and socio-economic advances. President Grant’s administration leveraged the power of the newly-formed Department of Justice and the U.S. military to ensure freedman could exercise their new right to vote in the South.

But relentless racial violence in the South and increasing antipathy in the North towards Reconstruction and the military involvements and occupation that it was continuing to require rendered many of those Reconstruction advances unsustainable by the end of Grant’s second term as president.5

Nonetheless, as historian Richard N. Current said of Grant: “By backing Radical Reconstruction as best he could, he made a greater effort to secure the constitutional rights of blacks than did any other President between Lincoln and Lyndon B. Johnson.”6

Also as President, Grant appointed a record number of Native, Jewish, and African Americans to government positions, including Ely Parker, the first Native American appointed to a presidential cabinet position. A delegation of Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, and Creeks described President Grant has having a “just and humane” approach to their people, “an earnest wish for their advancement,” “a conscientious regard for their rights,” and a desire “to enforce in their behalf, the obligations of the United States.”7

During Grant’s presidency, more Jews were appointed to government positions than probably all previous presidents’ Jewish appointees combined. Appointments included Simon Wolf, to the position of Recorder of Deeds, who also became Grant’s main advisor on Jewish affairs.8 Grant was the first U.S. president to attend a synagogue service while in office. When Grant died in July 1885, the Philadelphia Jewish Record stated, “None will mourn his loss more sincerely than the Hebrew.” One motivation for Grant’s positive presidential record on Jewish-American affairs was embarrassment over an egregiously anti-Semitic order he issued during the Civil War, and that President Lincoln quickly had Grant’s superior countermand.

The number of Black Americans appointed to government positions was astounding under Grant. Frederick Douglass, the great Black abolitionist, author, orator, and statesman, said, “In one Department at Washington I found 249, and many more holding important positions in its service in different parts of the country.” Douglass later eulogized Grant, saying, “In him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.”9

Nonetheless, Grant’s policies towards Native Americans, while comparatively progressive for his day, were sorely lacking and paternalistic, aimed completely at assimilation and so-called domestication, and not preservation of tribes, and Grant did little to directly intercede to stop the flow of white settlers into the areas where the Plains Indians lived.

Grant as U.S. president remained a calming figure for an anxious nation during the constitutional crisis of 1876–1877, which many Americans feared might combust into a second civil war.

Following the 1876 presidential election, both Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic Party’s candidate, and Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican Party’s candidate, claimed victory after Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina produced contested election results. Grant refused to show any favoritism towards Hayes, even though Hayes was a fellow Republican, and proposed a bipartisan Electoral Commission to determine the winner.10 The crisis ended with the Compromise of 1877, and the commission decided the presidency for Hayes, though as an unwritten condition of the settled contest, Hayes had to pledge to serve only one term and to officially end Reconstruction and the presence of U.S. troops in Southern states.

However, Grant’s administration, especially in the final years of his second term, was beset by scandals. Though Grant was not involved in illegality himself and did not personally or politically benefit (quite the opposite) from the shenanigans of some of his administration officials, the scandals revealed Grant’s tendency toward naivety regarding others’ intentions, and the sometimes resulting slowness on Grant’s part in acknowledging appointees’ corruption when presented with evidence.

Nonetheless, President Grant was also “a good steward of the nation’s finances,” as noted by Grant biographer Ron Chernow. Grant “slashed taxes, trimmed [the national] debt, and watched [America’s] trade balance turn from deficit to surplus.”11 After the Civil War, the U.S. government carried an enormous financial debt, but President Grant showed that the government could make good on its pledges to repay debt, which restored America’s credit and helped secure foreign capital needed for America’s modernization and expansion.12

During Grant’s presidency, he also “made a good-faith effort to eradicate corruption on [Native American] reservations by appointing agents chosen by religious groups.13

President Grant and his Secretary of State Hamilton Fish set a new standard in international relations by using arbitration and avoiding the threat or use of of force as a means of settling a dispute with Great Britain that stemmed from the Civil War. This also inaugurated the beginning of a new, cooperative Anglo-American relationship that endures to this day.14

As President, Grant also established the eight-hour workday. While his proclamation applied only to government workers—only the Congress could create such laws as would directly or through an empowered federal government agency affect the entire nation’s workforce—it was a significant leap forward in fair setting fair labor practices.

During Grant’s administration, the U.S. and Hawai’i (The Sandwich Islands) signed the Reciprocity Treaty, which gave the U.S. land that would later become Pearl Harbor naval base.15 Grant and First Lady Julia Grant also hosted King Kalakaua of The Sandwich Islands at the first State Dinner at the White House, on December 22, 1874.16

Grant and Alexander Robey Shepherd of the Board of Public Works enhanced the nation’s capital. They “adorned public parks with trees and shrubbery, straightened a third of the city’s roads, laid sidewalks where none had existed, introduced many streetlights” and Grant “signed legislation to finish the Washington Monument.”17

During Grant’s presidency, both the Department of Justice and the Weather Bureau (now known as the National Weather Service) were created, as was Yellowstone National Park, America’s first national park.

In America’s 1868 presidential election, Ulysses S. Grant and his running mate Schuyler Colfax, the speaker of the House of Representatives, ran as the Republican Party’s nominees for U.S. president and vice president respectively. The Democratic Party nominated Horatio Seymour, a former governor of New York, as its presidential nominee, and Francis Preston Blair Jr., a former Missouri congressman and, like Grant, a veteran of the Civil War.

Grant won 52.7% of the popular vote, and 26 states to Seymour’s eight.

In 1872, Ulysses S. Grant ran again as the Republican nominee. His vice-presidential running mate was U.S. senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, who had also been a Union officer in the Civil War. Grant’s presidential opponent was Horace Greely, an influential newspaper editor and publisher. Greeley ran as the nominee of both the Democratic Party and the Liberal Republican Party, which was formed by Republicans opposed to President Grant, whose presidential administration had been wracked by scandals and had taken strong and controversial political and military measures in the South to protect Blacks against racial violence. The vice-presidential nominee was Missouri’s governor Benjamin Gratz Brown, who had been a Union colonel in the Civil War.

Grant won 55.6% of the popular vote. The Seymour-Brown ticket won 43.8% of the popular vote but failed to carry even one state.

Ulysses S. Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, to Jesse Root Grant and Hannah Simpson Grant. The year after Grant was born, Jesse moved the family to Georgetown, Ohio, where Grant was raised.

Some days after Grant’s birth, his family gave him the name Hiram Ulysses Grant, though he went by “Ulyss” and “Lyss.”18

When the 17-year-old Grant arrived for training at the U.S. Military Academy, he noticed that his name had been officially but erroneously provided to the academy as “Ulysses S. Grant,” which he used as his name for the rest of his life. Grant’s initials, “U.S.” put his West Point classmates in mind of Uncle Sam, the popular personification of the U.S. government. So they nicknamed him “Sam.”19

This means that Grant’s middle initial “S” does not stand for anything. However, his mother had taken her maiden name, Simpson, as her middle name—a not infrequent practice in those days—and one of his brothers was named Simpson, after Hannah’s side of the family.

Ulysses S. Grant died of throat cancer on July 23, 1885, in Wilton, New York, at the woodland, mountainside cottage of Joseph W. Drexel, a friend of Grant’s who lent it to the Grants for their use during the final months of Ulysses S. Grant’s life. At the time, the Grant’s officially resided at 3 East 66th Street in New York City, New York, right off Fifth Avenue, very near to Central Park and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ulysses S. Grant is interred in a red granite sarcophagus in the General Grant National Memorial, commonly called Grant’s Tomb, a mausoleum in Riverside Park, New York City, New York. His wife Julia Dent Grant lies in a matching sarcophagus beside him. Grant’s Tomb is the largest mausoleum in the Western Hemisphere and is 150 feet tall. The sarcophagi are slightly raised above the memorial’s floor, positioned under the mausoleum’s interior dome, and easily viewable from the public gallery above.

“Who’s buried in Grant’s tomb?” was a popular trivia question used by comedian Groucho Marx as the host of radio and television quiz shows in the late 1940s and 1950s. Technically, the answer to the question is “no one.” Since Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant are in sarcophagi above ground, they are entombed, not buried, in Grant’s Tomb.20

Yes, Ulysses S. Grant has living relatives. Grant and his wife Julia Boggs Grant (née Dent) had four children and 12 grandchildren.

One of Grant’s living descendants today is Ulysses Grant Dietz, Ulysses S. Grant’s great-great grandson, a curator and writer, residing in New Jersey, who serves on the board of the Ulysses S. Grant Association.

The annual meeting of the Ulysses S. Grant Association can be an occasion to meet living relatives of Ulysses S. Grant.