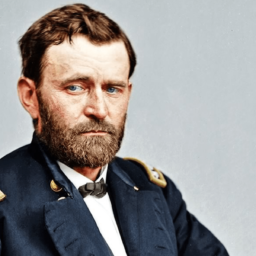

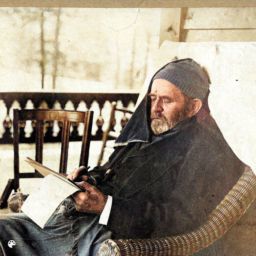

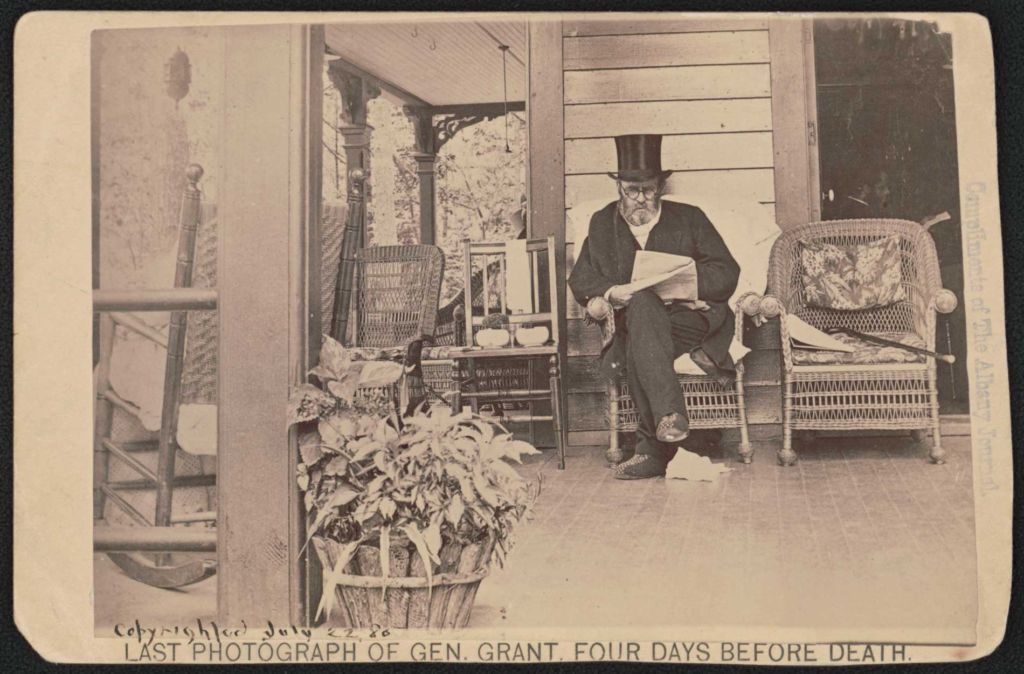

Mt. McGregor, New York. On July 19, 1885, photographer John G. Gilman for the Albany Journal, took the last known photograph of Ulysses S. Grant. In the photo, a spectacled Grant wears a black suit and stovepipe hat, despite the warm weather, and slippers, as he sits in a rattan chair reading a newspaper on the porch of the cottage in which he would die of cancer just four days later.

Grant had just finished the manuscript of his 336,000-word memoirs, a task begun only about a year before (Chernow 951). He had soldiered through the Herculean task amid the agony, including suffocation-like sensations, of terminal throat cancer.

Grant’s determination sprang from some desperation. Only months before his cancer arose, a Wall Street schemer had defrauded Grant and his wife Julia out of virtually every penny they had. At that point, the Grants had no source of income, since presidents did not get a pension then. In part through the assurances of his publisher Mark Twain, Grant came to realize that sales of his memoirs could provide a financially secure widowhood for the former First Lady.

Harrison Terrell

Grant on June 2, 1885, had penned to Terrell a letter of reference and gratitude:

I give this letter to you now, not knowing what the near future may bring to a person in my condition of health. This is an acknowledgement of your faithful services to me during my sickness up to this time, and which I expect will continue to the end. This is also to state further that for about four years you have lived with me, coming first as a butler, in which capacity you served until my illness became so serious as to require the constant attention of a nurse, and that in both capacities I have had abundant reason to be satisfied with your attention, integrity and efficiency. I hope that you may never want for a place. Yours, U.S. Grant. (Trimm 27)

As noted in “Judged By Merit,” an article on the Grant Cottage website, following Grant’s death on July 23, 1885, Harrison would by 1886 secure a position within the Paymaster General’s office at the War Department in Washington, D.C. Then:

Within three years Harrison was an Assistant Messenger at the War Department with an annual salary of $720, higher than the average wage for most U.S. citizens at a time when income for African Americans per capita in the US was 34% that of white Americans. (February 27, 2021)

Though Grant would not live to see it, Harrison’s son, Robert, would become accomplished. He would serve as justice of the peace for the District of Columbia:

and later under President Taft he would become the first Federally-appointed African American municipal judge for the district. Robert also helped found the American Negro Academy and lectured and advocated for the honest scholarship of African American history. (Ibid.)

Assessments slightly vary as to when Grant set aside his writing implements at the cottage at Mount McGregor, New York, which is near Saratoga Springs and where Grant spent his final few weeks of life. (Today, the cottage is preserved as the U.S. Grant Cottage National Historic Landmark.)

Ron Chernow in Grant (2017) writes, “On July 16, he put down his pen, his mighty labor over, and informed Dr. Douglas that he was ‘not likely to be more ready to go than at this moment.’” (952)

Mark Perry, in Grant and Twain (2004)—cited also by Louis Picone in Grant’s Tomb (2021)—writes that on July 19, Grant “put down his pencil and looked at Dawson. He smiled a bit, looked back down at his paper, and then handed it to the transcriber. The book was finished, he said. He had done as much as he could” (225).

Brett Baier and Catherine Whitney in To Rescue the Republic (2021) also mark July 19 as Grant’s final day of writing, stating that on that day, “curled in a chair, his frail body weighing less than one hundred pounds, Grant pressed the lead of his pencil firmly onto the page and wrote his final words” (323).

Ronald C. White, Jr. in American Ulysses (2016) writes of Grant’s July 16 note to Dr. Douglas but not of when Grant’s last day of writing may have been:

On July 16, Grant admitted to Douglas that earlier, in his weakened condition, “my work had been done so hastily that much was left out,” but now it pleased him that “I have added as much as fifty pages to the book.” (651)

The Instagram account of Grant’s Tomb (National Park Service), posted yesterday that on July 18, 1885, “President Ulysses S. Grant is thought to have completed the final proofreading of his two-volume autobiography the ‘Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant.’” To be sure, final proofreading and the last day of writing may not be considered the same thing, and I do not mean to suggest that the Tomb’s post is conflating them.

I note that on July 19, Grant wrote to Dr. John H. Douglas about writing, but that surely does not relate to any writing of his memoirs. Grant at this point wrote many notes, since his cancer had mostly robbed him of the ability to speak.

If that is the case do you not think it advisable for me to get up and rest as the tailor does—when he is standing up. . . . I can however write better seated with the board before me. I do not think I should take my medecine now. I might try to go to sleep and when I want the medecine call you. (Papers 439)

Whatever the date that General and President Grant set aside his memoirs project for good, July 16, 18, or 19, the famous photograph remarkably records U.S. Grant—along with Harrison Terrell close at hand—with his great literary feat behind him but acutely aware that he had only a short while left to live.

Postscript

See below.

IMAGE

Gilman, John G. Last photograph of Gen. Grant, four days before death / Gilman, Mt. McGregor and Canajoharie, N.Y., 1885. Albumen silver print. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005694591/.

SOURCES

Baier, Bret. To Rescue the Republic: Ulysses S. Grant, the Fragile Union, and the Crisis of 1876. Custom House, 2021. Kindle.

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

@grantstombnps. “An able critic told me the other day.” Instagram, July 18, 2022. https://www.instagram.com/p/CgJ_vCHPT89/.

Picone, Louis L. Grant’s Tomb: The Epic Death of Ulysses S. Grant and the Making of an American Pantheon. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2021. Kindle.

Simon, John Y., “The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 31: January 1, 1883–July 23, 1885” (2009). Volumes of The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. 30.

https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usg-volumes/30.

Trimm, Steve. General Grant’s Supporting Players. Friends of The Ulysses S. Grant Cottage, 2019.

U.S. Grant Cottage National Historic Landmark (website). “Judged By Merit.” February 27, 2021. Accessed July 19, 2022. https://www.grantcottage.org/blog/2021/2/27/judged-by-merit.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2016. Kindle.

Postscript

I noticed that the Library of Congress’s record information for the July 19, 1885, photograph of Grant did not mention Harrison Terrell. I reached out to the Library with the following message:

Could the records for http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/

A former slave, Terrell had since the early 1880s been a paid servant among the small household staff of Ulysses and Julia Grant. When the Grants went broke and could no longer pay wages, Terrell stayed anyway, determined to help.

It is appropriate to mention Harrison Terrell in the library’s record for these images.