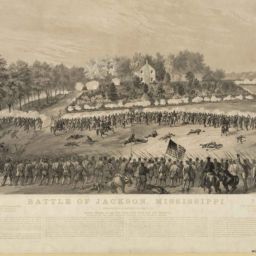

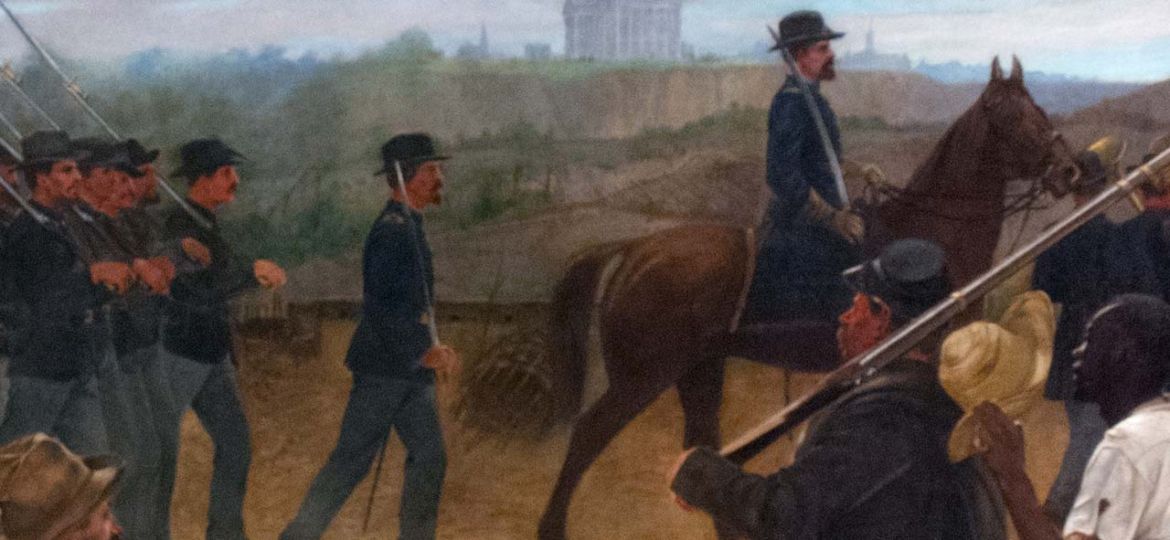

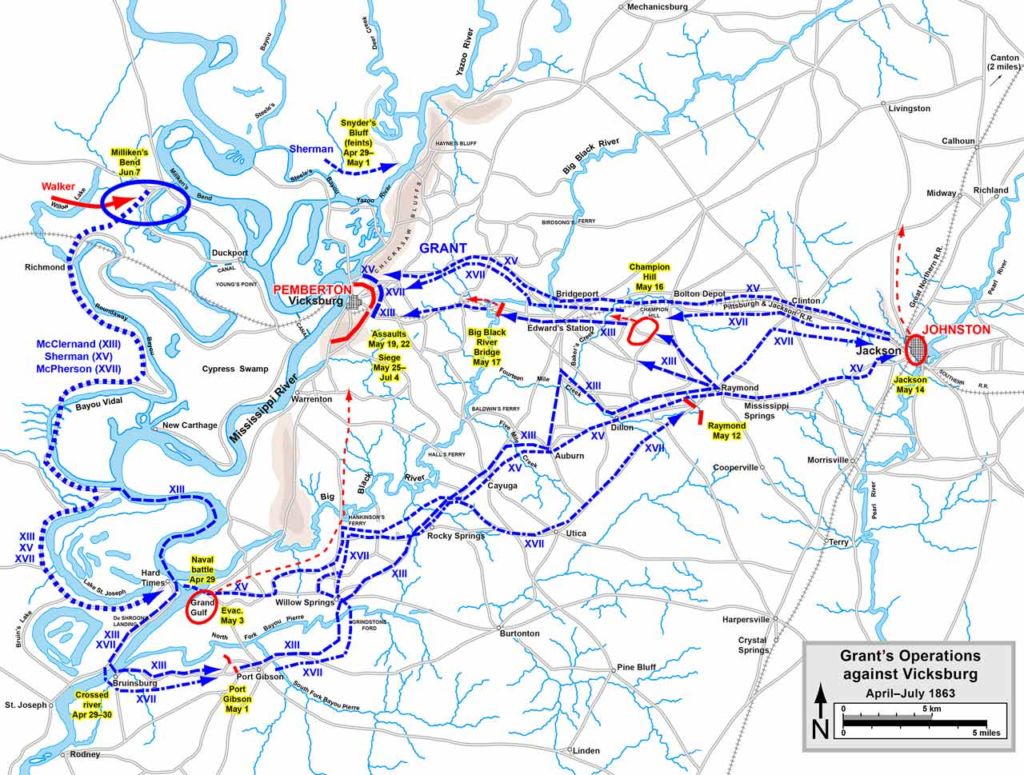

American Civil War, Western Theater, Vicksburg campaign. On July 4, 1863, the Confederate garrison in Vicksburg, Mississippi, surrendered to Major General Ulysses S. Grant.

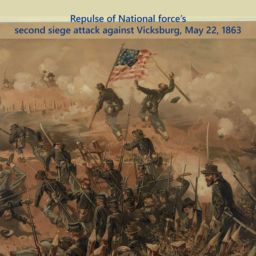

Following Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s battlefield victories at Champion Hill on May 16, 1863, and Big Black River Bridge on May 17, the bulk of the Confederate forces in Mississippi, under the command of John Pemberton, had been effectively bottled up inside Vicksburg. After failed assaults against the city on May 19 and 22 by his forces—the Army of the Tennessee—Grant ordered that Vicksburg be besieged and thereby compelled to surrender.

Grant’s siege of Vicksburg followed 18 days of rapid movement and fighting by his army while it was detached from its lines of communication—i.e., exterior routes for the army’s supplies, reinforcements, and information. Once the siege started, Grant began to open up his supply lines from the Mississippi river-port town of Grand Gulf, south of Vicksburg. As a result, after the Confederate garrison in Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, the 48th day after the siege of Vicksburg had begun, Grant was able to promptly begin to supply the garrison and the town’s citizens with food.

“Here, Reb, I know you are starved nearly to death.”

Jerry Korn in War on the Mississippi: Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign,

When the Federal soldiers arrived [inside Vicksburg], their behavior was impeccable. “No word of exultation was uttered to irritate the feelings of the prisoners,” wrote the Confederates’ Sergeant Tunnard in some wonder. “The the contrary, every sentinel who came upon post brought haversacks filled with provisions, which he would give to some famished Southerner with the remark, ‘Here, Reb, I know you are starved nearly to death.’”

Colonel Samuel Lockett, Pemberton’s chief engineer, later remembered that the only Federal cheers he heard that day came from a Union outfit that raised a shout “for the gallant defenders of Vicksburg.” (156–157)

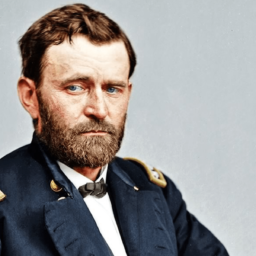

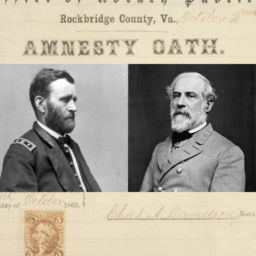

Hirsute Ulysses S. Grant Gets a Haircut

Ronald C. White, Jr., in American Ulysses, provides further details about Grant’s victory at Vicksburg:

Grant gave [Major General] John Logan, whose [3rd Division of James B. McPherson’s XVII Corps] had come nearest to breaking through [Vicksburg’s] defenses, the honor of marching his division first into the city. Grant rode in and watched his men share their rations with hungry Confederate soldiers. He was pleased: “The men had behaved so well that I did not want to humiliate them. . . . ”

He went to the waterfront and rode up the gangplank to congratulate [Acting Rear Admiral David Dixon] Porter and his sailors on his new flagship, the Black Hawk. Porter opened all his wine lockers but recalled that “General Grant was the only one in that assemblage who did not touch the simple wine offered him,” contenting himself with a cigar. In the midst of the exhilaration, Porter noticed “there was one man there who preserved the same quiet demeanor he always bore, whether in adversity or victory, and that was General Grant.” The admiral thought to himself, “No one, to see him sitting there with that calm exterior, amid all the jollity . . . would ever have taken him for the great general who had accomplished one of the most stupendous military feats on record.” (White 286–287)

Ron Chernow, in Grant, provides an interesting anecdote that seems quintessentially Grant:

Grant impressed most folks in Vicksburg with his unassuming, egalitarian nature. When he went to a barbershop [in Vicksburg] for a haircut, an aide tried to shove Lieutenant Frank Parker from a chair to make room for him, but Grant refused to brush aside a junior officer. “You are all right, my friend; go ahead,” Grant said. “You feel just as much like getting cleaned up as any general, and you have got as much right to your turn as I have to mine.” Parker was touched, since the hirsute Grant desperately needed a barber’s attention. “He looked rough . . . his beard was long and his hair was ragged and his clothes were dusty and faded, but he never put on airs and never assumed to be a general.” (Chernow 291)

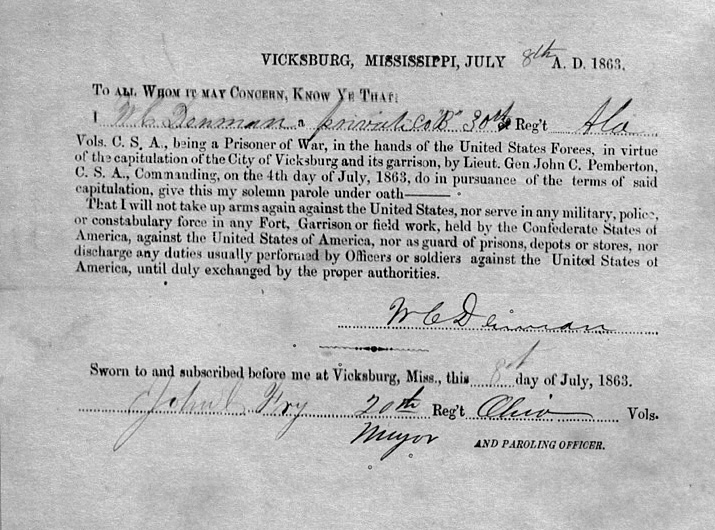

Paroling the Former Confederate Garrison of Vicksburg

Now Grant had to face the administrative and other practical consequences of having tens of thousands of surrendered Confederate troops to deal with. Grant wrote in Personal Memoirs:

On the afternoon of the fourth [of July] I sent Captain Wm. M. Dunn of my staff to Cairo, the nearest point where the telegraph could be reached, with a dispatch to the general-in-chief [Major General Henry Halleck]. It was as follows: “The enemy surrendered this morning. The only terms allowed is their parole as prisoners of war. This I regard as a great advantage to us at this moment. It saves, probably, several days in the capture, and leaves troops and transports ready for immediate service. [Major General William Tecumseh] Sherman, with a large force, moves immediately on [Confederate general Joseph Eggleston] Johnston, to drive him from the State. . . .” This news, with the victory at Gettysburg [in Pennsylvania] won the same day, lifted a great load of anxiety from the minds of the President, his Cabinet and the loyal people all over the North. The fate of the Confederacy was sealed when Vicksburg fell. Much hard fighting was to be done afterwards and many precious lives were to be sacrificed; but the MORALE was with the supporters of the Union ever after.

. . . . .

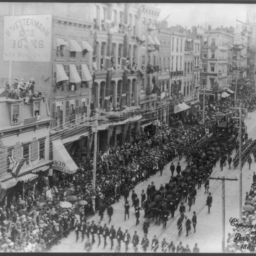

Pemberton and his army were kept in Vicksburg until the whole could be paroled. The paroles were in duplicate, by organization (one copy for each, Federals and Confederates), and signed by the commanding officers of the companies or regiments. Duplicates were also made for each soldier and signed by each individually, one to be retained by the soldier signing and one to be retained by us. Several hundred refused to sign their paroles, preferring to be sent to the North as prisoners to being sent back to fight again. Others again kept out of the way, hoping to escape either alternative. . . .

As soon as our troops took possession of the [city,] guards were established along the whole line of parapet, from the [Mississippi] river above to the river below. The prisoners were allowed to occupy their old camps behind the intrenchments. No restraint was put upon them, except by their own commanders. They were rationed about as our own men, and from our supplies. The men of the two armies fraternized as if they had been fighting for the same cause. When they passed out of the works they had so long and so gallantly defended, between lines of their late antagonists, not a cheer went up, not a remark was made that would give pain. Really, I believe there was a feeling of sadness just then in the breasts of most of the Union soldiers at seeing the dejection of their late antagonists. (Grant 567–570)

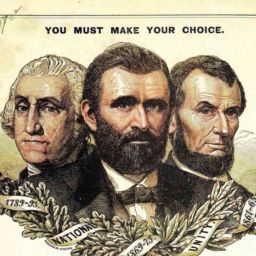

“Grant is my man, and I am his the rest of the war,” President Abraham Lincoln

Americans both of North and South knew the strategic significance of Vicksburg. The South dreaded hearing of Vicksburg’s fall. The North had hoped for it, including the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln.

The glad tidings brightened the mood of Lincoln, who had been so worried about Vicksburg that his eyelids drooped and dark rings encircled his eyes. He was studying a map of Mississippi when a beaming [Secretary of War] Gideon Welles pranced in with a telegram from Admiral Porter fluttering in his hand. He executed a little jig and threw his hat into the air: “I have the honor to inform you that Vicksburg has surrendered to the U.S. forces on this 4th day of July.” With a double dose of fantastic news from Vicksburg and Gettysburg, Lincoln, nearly euphoric, embraced Welles, proclaiming, “I cannot, in words, tell you my joy over this result. It is great, Mr. Welles, it is great!”

. . . . .

On July 13, thankful for Vicksburg, Lincoln composed a noble letter to Grant: “I do not remember that you and I ever met personally. I write this now as a grateful acknowledgment for the almost inestimable service you have done the country.” Lincoln admitted magnanimously that he had faulted Grant’s strategy, believing that, after crossing the Mississippi, he should have moved south and hooked up with [Major General Nathaniel Prentice] Banks instead of shooting northeast toward Jackson. “I feared it was a mistake—I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that you were right, and I was wrong. Yours very truly. Abraham Lincoln.” (Chernow 292–293)

It is the broad consensus among Civil War historians, supported by the historical record, that with the fall of Vicksburg, the President’s strong confidence in Ulysses S. Grant became, for all intents and purposes, utterly unshakeable barring some unimaginable error of gross incompetence of Grant’s part.

“Grant is my man,” Lincoln insisted, “and I am his the rest of the war.” (Chernow 292)

IMAGES

Millet, Francis D. The Fourth Minnesota Entering Vicksburg, c. 1904. Oil on canvas, 6’8” x 8’4”. Governor’s Reception Room, the Minnesota State Capitol, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.A. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Millet-The_Fourth_Minnesota_Entering_Vicksburg_After-Restoration.jpg.

Parole card of 26-year-old William C. Denman (1836–1906). Andy Hall. “Paroled at Vicksburg.” Dead Confederates. (Blog.) July 5, 2010. https://deadconfederates.com/2010/07/05/paroled-at-vicksburg/.

SOURCES

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Korn, Jerry. War on the Mississippi: Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books Inc., 1985.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2016. Kindle.