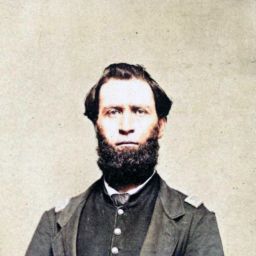

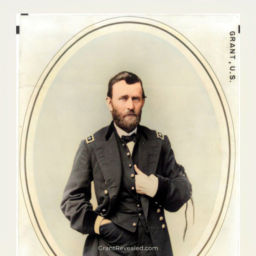

American Civil War, Western Theater, Vicksburg Campaign. The Battle of Raymond, Mississippi, on May 12, 1863, altered Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s short-term strategy for capturing the vital Confederate railroad hub and riverside city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. As Grant wrote in his memoirs:

As I hoped in the end to besiege Vicksburg I must first destroy all possibility of aid. I therefore determined to move swiftly [eastward] towards Jackson, [Mississippi,] destroy or drive any force in that direction and then turn [back westward] upon [Confederate Lieutenant General John C.] Pemberton [near Vicksburg]. But by moving against Jackson, I uncovered my own communication. So I finally decided to have none—to cut loose altogether from my base and move my whole force eastward. I then had no fears for my communications, and if I moved quickly enough could turn upon Pemberton before he could attack me in the rear.

Pultizer Prize-winning author Ron Chernow in his biography Grant describes how on the evening of May 13, “Grant’s soldiers waded through foot-deep puddles in a rainy, headlong rush toward the state capital.”

That same evening, the Confederate commander General Joseph Eggleston Johnston decided that the city of Jackson could not be successfully defended and began withdrawing his troops from there, northward. An exodus of civilians from Jackson had already occurred.

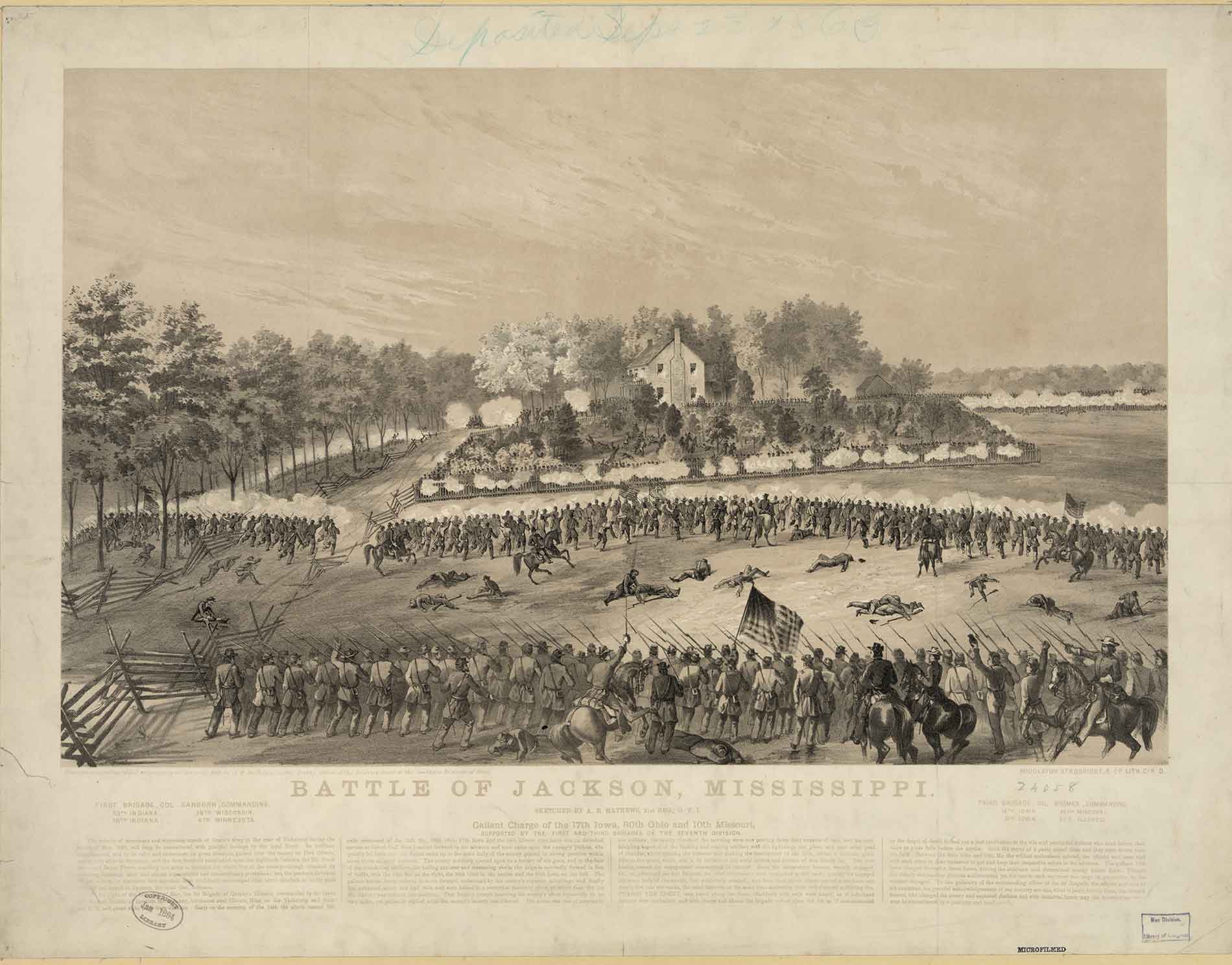

Grant had ordered major generals Sherman and McPherson to hit Jackson hard at dawn. They did so. Grant describes in his memoirs in some detail their battle against Brigadier General John Gregg’s force that Johnston had committed to a rearguard defense of Jackson to slow down the Union advance.

Nonetheless, as Chernow summarizes, “Jackson collapsed with stunning speed, becoming the third southern capital after Nashville and Baton Rouge to succumb….”

Grant continues in his memoirs:

I rode immediately to the State House, where I was soon followed by Sherman. About the same time McPherson discovered that the enemy was leaving his front, and advanced…so close upon the enemy that they could not move their guns or destroy them. He captured seven guns and, moving on, [men of the 59th Regiment, Indiana Volunteer Infantry,] hoisted the National flag over the rebel capital of Mississippi.

Grant states that “loss in this engagement was” 41 killed, 228 wounded, all from McPherson’s corps, with another “21 wounded and missing,” from Sherman’s.

The enemy lost 845 killed, wounded and captured. Seventeen guns fell into our hands, and the enemy destroyed by fire their store-houses, containing a large amount of commissary stores.”

Ronald C. White in his biography, American Ulysses writes:

That evening, at the Bowman House, Grant slept on a mattress for the first time in weeks, in the room occupied by Johnston the night before. The next morning, he left Sherman in charge of Jackson with orders to put the torch to all railroad and manufacturing, including an iron foundry, carriage factory, and paint and carpenter shops.

But at least one instance of such destructive work began the afternoon before, as Grant describes in his memoirs.

Sherman and I went together into a manufactory which had not ceased work on account of the battle nor for the entrance of Yankee troops. Our presence did not seem to attract the attention of either the manager or the operatives, most of whom were girls. We looked on for a while to see the tent cloth which they were making roll out of the looms, with “C. S. A.” woven in each bolt. There was an immense amount of cotton, in bales, stacked outside. Finally I told Sherman I thought they had done work enough. The operatives were told they could leave and take with them what cloth they could carry. In a few minutes cotton and factory were in a blaze. The proprietor visited Washington while I was President his pay for this property, claiming that it was private. He asked me to give him a statement of the fact that his property had been destroyed by National troops, so that he might use it with Congress where he was pressing, or proposed to press, his claim. I declined.

William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel in Vicksburg Is the Key summarize the situation after the Grant’s victory at Jackson.

By nightfall on May 15, seven Union divisions—about thirty-two thousand men—were camped on a line from Bolton to Raymond, facing west…. The stage was set for the climactic battle that would decide the fate of Vicksburg.

Citations:

Ron Chernow, Grant (New York: Penguin Books, 2017), 263. Kindle.

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885), 1:499, 506, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015010484130&view=1up&seq=9&skin=2021.

William L. Shea, Terrence J. Winschel, Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 131.

Ronald C. White Jr., American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2016), 275. Kindle.