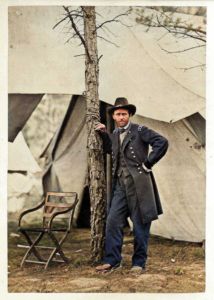

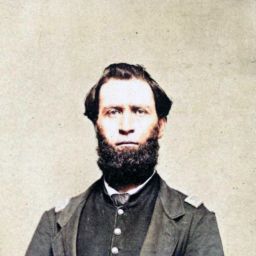

On the morning of June 12, 1864, the Washington, D.C.-based photographer Mathew Brady achieved the American Civil War’s best-known portrait of a commander in the field. (White 364)

Brady’s subject, Ulysses S. Grant, the 42-year-old head of the U.S. Army, stood outside of his headquarters near Cold Harbor, Virginia. It was a Sunday and the final day of what history calls his Overland campaign.

Since May 4, Grant had been driving southward through Virginia, fighting his way towards Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the confederacy of Southern states in secessionist rebellion since spring 1861.

In the photo, Grant gazes out of frame, his left hand on his hip, his right raised nearly to eye level against a tree with his tent fly’s guy rope wrapped around it. His slouch hat sits slightly back on his head. Grant as usual wears neither sash nor sword.

Theodore Lyman III stood nearby. An aide-de-camp to Grant’s colleague Major General George Meade, Lyman before the war graduated near the top of his class at Harvard and then helped found the school’s Museum of Comparative Anatomy. He’d once studied starfish in Florida. A keen observer and correspondent, on June 12, he studied three-starred Grant instead, writing:

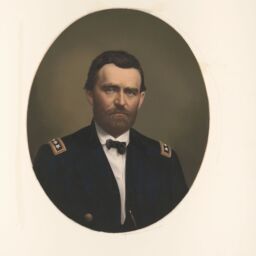

General Grant has appeared with his moustache and beard trimmed close, giving him a very mild air — and indeed he is a mild man really. He is an odd combination; there is one good thing, at any rate — he is the concentration of all that is American. He talks bad grammar, but he talks it naturally, as much as to say, “I was so brought up and, if I try fine phrases, I shall only appear silly.” Then his writing, though very terse and well expressed, is full of horrible spelling. In fact, he has such an easy and straightforward way that you almost think that he must be right and you wrong, in these little matters of elegance. . . . (Lyman 156)

In the famous photo, Grant’s careworn face conveys the past 38 days’ relentlessly grueling contest of complex military maneuvers and his army’s three successive battles, each among the bloodiest of the Civil War, against the Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Robert E. Lee.

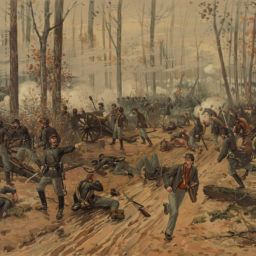

At the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5–7), Union and Confederate forces clashed among thick tree growth for hours, sometimes firing at each other at nearly point-blank range. Sparks ignited brush fires, their smoke further obscuring sight. The fires continued at night, burning alive the wounded still immobilized on the battlefield. Their screams were clearly heard amid the fighting’s lull.

Following the inconclusive battle, Grant did what no Union commander before had done. He pressed on.

His predecessors had always fallen back to regroup and reinforce after such pounding battles when they also tried to reach Richmond or destroy Lee’s army. But each time they did so, it let the enemy do the same. Each time, it in effect prolonged the war. Each time, it gave the Southern insurrection more opportunity to ask foreign powers to recognize Confederate nationhood. Each time, it let accommodationist opponents of President Abraham Lincoln further organize against him and the now hybrid cause of perpetual American Union and national abolition of slavery.

After the Wilderness, Grant wheeled his 100,000-man Army of the Potomac around Lee’s army’s right flank. Both armies raced to the key crossroad village of Spotsylvania Court House. But Lee’s men arrived first, just barely.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House ensued (May 9–21, 1864). Though outnumbered, Lee’s army gained profound advantage from its earthworks along their long defensive line shaped like an inverted-V, including a half-mile bulge, or salient, at its tip, dubbed the “mule shoe” by the soldiers who endured the slaughterous fighting there.

The battle’s several days saw at best fleetingly successful Union attacks and inconclusive Confederate countercharges. On May 12, combined Union and Confederate casualties—men killed, wounded, captured, or missing—numbered 17,000 over the course of 22 hours.

Gregory Jaynes in The Killing Ground writes:

When the morning of May 13 dawned over the salient, the Federal troops awoke to find nothing but corpses in it. In one part of [it] measuring no more than 12 by 15 feet they discovered 150 bodies. A Pennsylvanian recalled seeing rifle pits filled with corpses eight to 10 deep. A Maine lad looking for a friend found a corpse so shot up “there was not four inches of space about this person that had not been struck by bullets.”

Jaynes quotes Lieutenant Colonel John Schoonover of the 11th New Jersey Infantry Regiment:

“The trees near the works were stripped of their foliage, and looked as though an army of locusts had passed.

. . . . .

“The brush between the lines was cut and torn into shreds, and the fallen bodies of men and horses lay there with the flesh shot and torn from their bones.” (Jaynes 105)

Once again, as he did after the Wilderness, Grant after Spotsylvania pressed on, again moving by his left flank, that is, to the east, inching closer towards Richmond and denying Lee the initiative.

During these maneuvers, elements of Grant’s and Lee’s armies fought a series of smaller engagements, but without a general one between the two armies, collectively known as the Battle of North Anna (May 23–26). Grant got his army across the North Anna river with the aid of pontoon bridges, and continued his advance.

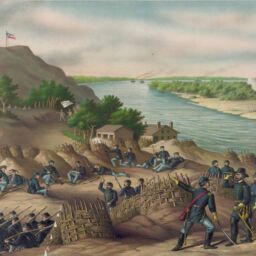

Then came the Battle of Cold Harbor. It, too, lasted for days, like the other Overland battles, and began on May 31. The fighting was at its worst on June 3. During one 20-minute period on that day, one attacking Union division, commanded by John Gibbon, of the II Corps under Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, suffered 1,000 casualties in 20 minutes, the equivalent of 50 men per minute. One Confederate artilleryman wrote that at every discharge of their cannons against the advancing Union attacks:

“heads, arms, legs, guns were seen flying high in the air. [The attackers] closed the gaps in their line as fast as we made them, and on they came, their lines swaying like great waves of the sea.” (161)

William Derby of the 27th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment wrote that the ground reminded him of “a boiling cauldron from the incessant pattering of shot which raised the dirt in geysers.” To Captain Charles Currier of the 40th Massachusetts, the Confederate fire “piled up our men like cordwood.” (164)

The Wilderness and Spotsylvania saw staggering losses on both sides and inconclusive outcomes. But at Cold Harbor, the Union army suffered far higher losses. In 1885, Grant wrote in his memoirs, “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. . . . [N]o advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.” (Grant 276)

Despite the defeat that Lee dealt Grant at Cold Harbor, he feared what Grant might do next. Grant was clearly unlike previous generals Lee faced. “We must destroy this Army of Grant before he gets to the James River,” Lee said. ” If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” (Jaynes 136)

On June 11, Grant informed his generals to again move by the left flank the next evening and laid out guidelines for the line of march. The objective: cross the James River, skirting around Richmond and striking at Petersburg, Virginia, south of it. (Simpson 405)

Ron Chernow in Grant:

By June 12, the weather had turned cool and windy. That night, after dark, Grant began to march his army toward the James. Staff officers noticed the tense way Grant relit cigars constantly and reacted with monosyllables. “Yes, yes,” or “Go on—go on.”

On this splendid night full of moonlight, the tramp of feet lifted swirling dust that soon obscured the stars. By the next morning, in a logistical masterpiece, the Army of the Potomac had vacated the Cold Harbor trenches. Lee was completely fooled by the exodus and thunderstruck to discover that Grant’s entire army of 115,000 men had vanished in the night. (411)

Ulysses S. Grant was about to make Robert E. Lee’s worst fears begin to come true.

Featured, cropped, and larger size below: Brady, Mathew. General Ulysses S. Grant at his headquarters in Cold Harbor, Virginia. June 12, 1864. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002736661/.

Inset: A version that I colorized via MyHeritage.com.

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Jaynes, Gregory. The Killing Ground: Wilderness to Cold Harbor. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books Inc., 1986.

Lyman, Theodore. With Grant and Meade from the Wilderness to Appomattox. Edited by George R. Agassiz. Original edition by Atlantic Monthly Press, Boston, 1922, entitled Meade’s headquarters, 1863–1865, letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from the Wilderness to Appomattox). http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2001.05.0069.

Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, (Military Classics). Zenith Press, 2014. Kindle Edition.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2016. Kindle.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Theodore Lyman III,” last modified December 15, 2021, at 20:51, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Lyman_III.