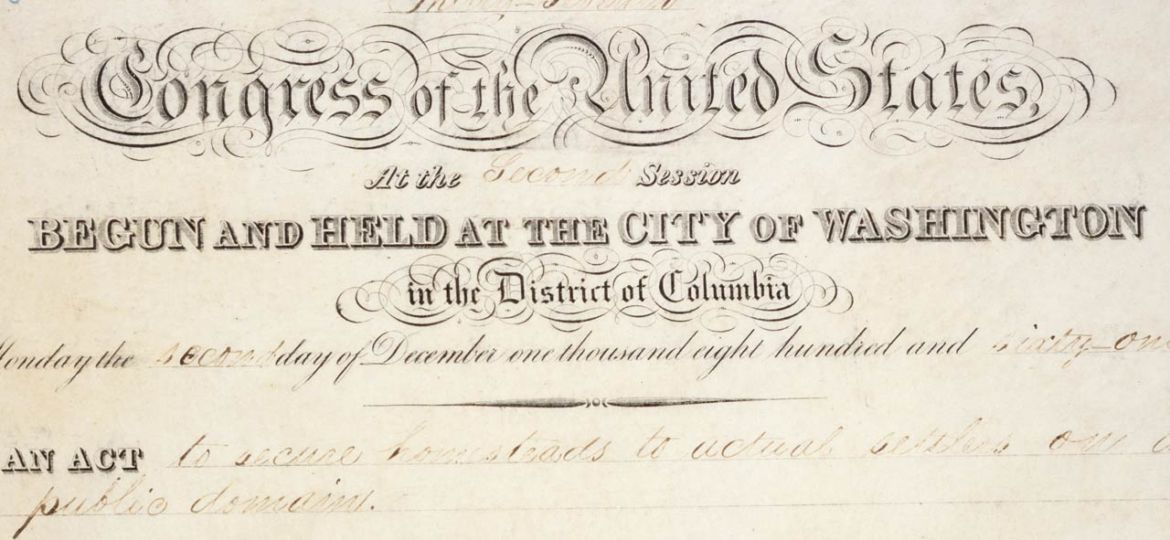

Washington, D.C. On May 20, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act. (Text of the act here.)

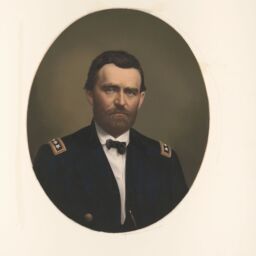

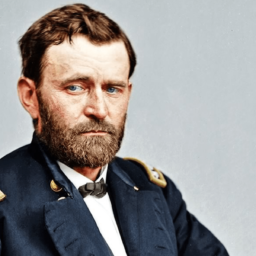

This act and the management of its consequences would have profound effects, including during the presidential administration of Ulysses S. Grant (1869–1877).

As Ron Chernow points out in Grant, along with the National Bank Acts and “the Morrill Act setting up land-grant universities,” the Homestead Act was part of a massive expansion of federal power that would test Grant’s “ability to manage.” By the time Grant took office:

Boasting fifty-three thousand employees, the federal government ranked as the nation’s foremost employer. Before the war, it had touched citizens’ lives mostly through the postal system. Now it taxed citizens directly, conscripted them into the army, oversaw a national currency, and managed a giant national debt…. When the first transcontinental railroad, aided by land grants and government bonds, was completed two months after Grant took office, it heralded a new geographic unity in American life. (644)

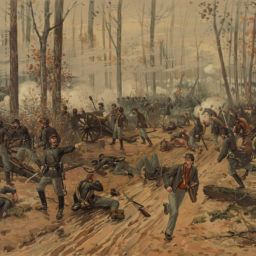

But the rushes for land that the Homestead Act and subsequent, related laws unleashed, massively took from Native Americans much of their land and the natural resources they depended on.

Chernow again, in Grant:

“I have lived with the Indians and I know them thoroughly,” [Grant] said. “They can be civilized and made friends of the republic.” He blamed white settlers for many problems wrongly attributed to Native Americans. Right after Appomattox, he remarked that “the Indians require as much protection from the whites as the white does from the Indians. My own experience has been that little trouble would have ever been had from them but for the encroachments & influence of bad whites.” He thought peace with the Indians could be achieved if only the latter renounced their “roving life” and agreed to “fixed places of abode” on reservations. [Grant’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Ely] Parker, espoused an end to the treaty system, contending that treaties could only be made between two sovereign states, whereas Indian tribes were “wards” of the American government.

Even as he enunciated his Peace Policy, Grant knew frightened settlers demanded tough federal protection and they constituted his ultimate political constituents. Over time, his genuine concern for Indian justice had to reckon with an incessant clamor from railroads, ranchers, and miners for more troops and frontier forts. Spurred by the 1862 Homestead Act and the transcontinental railroad, the country had made a tremendous investment in westward expansion, providing land for white settlers and masses of immigrants. Indians and federal soldiers would trade blows and engage in atrocities across a wide swath of territory. While preaching how it was “much better to support a Peace commission than a campaign against Indians,” Grant would be summoned repeatedly to send arms to western states to defend them against Indian raids. (658)

Sources:

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Kumar, Priyanka. “How Native Americans battled a brutal land grab by an expanding America.” Review of The Earth is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West, by Peter Cozzens. Washington Post, November 4, 2016.

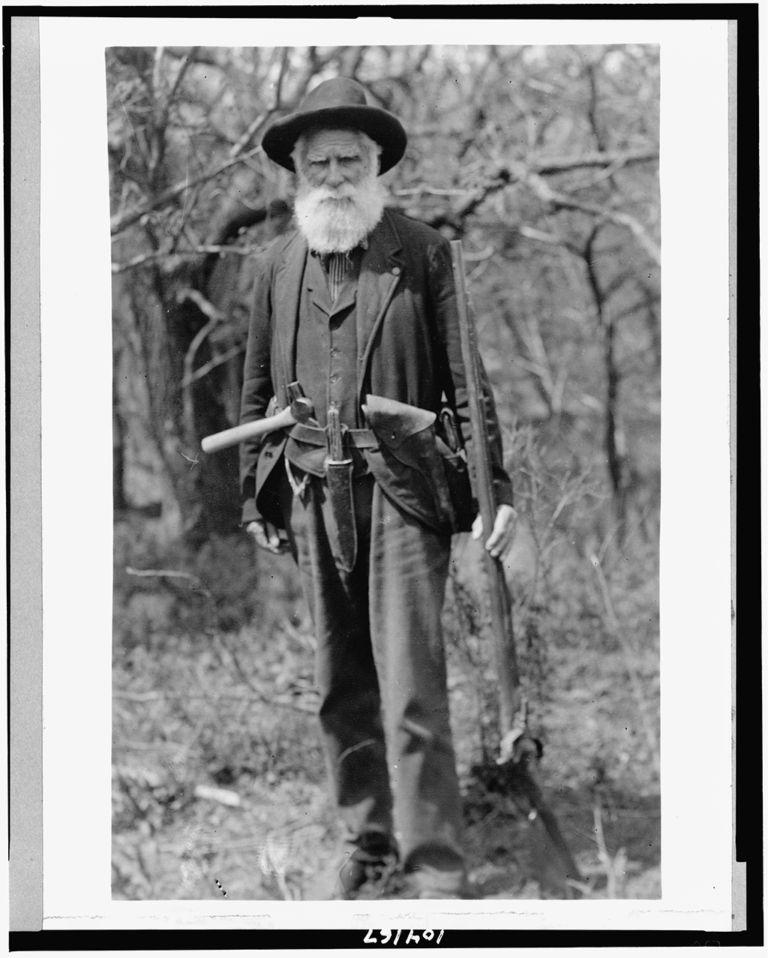

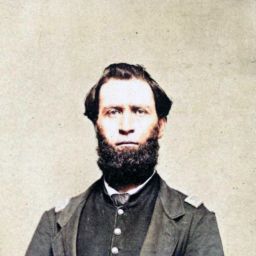

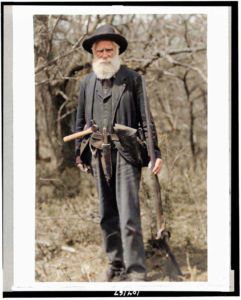

Inset photo 1, colorized, also below: Daniel Freeman standing, holding gun, with hatchet tucked in belt, c. 1904, photographic print, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/91783897/, “The ‘first homesteader’, who settled in Beatrice, Neb. 1863.” Verso of mat: “J.A. Ball, Beatrice, Neb.”

Inset photo 2, colorized: The first homestead in the United States, U.S.A., 1904, photographic print, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012646764/. “Daniel Freeman homestead in Gage County, Nebraska, the first homestead claim under the 1862 Homestead Act.”