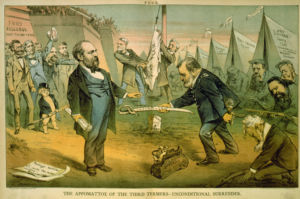

Post-presidency, Chicago, Illinois, Long Branch, New Jersey, and New York City, New York. Even among Americans who enjoy U.S. history, few know that Ulysses S. Grant sought a third, nonconsecutive term as U.S. president.

Following his presidency of 1869–1877, Grant undertook a two-year-long world tour—a first for any U.S. president. He set forth on May 17, 1877, aboard the American Steamship Company’s S.S. Indiana. He returned to the United States on September 20, 1879, aboard the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s iron steamship S.S. City of Tokio.

Back in the U.S.A., Grant enjoyed great acclaim and an improved political reputation. The latter had suffered significantly from corruption scandals that beset his presidency, especially in its second term. Grant neither partook in nor benefited from the corrupt dealings of administration officials. Nonetheless, shenanigans occurred on his watch, repeatedly. And they rightly raised complaints about Grant’s inconsistent abilities to judge men’s character or to advance reform and professionalization among the ranks of the federal government. Sometimes he had shown sagacity. Too often he had not.

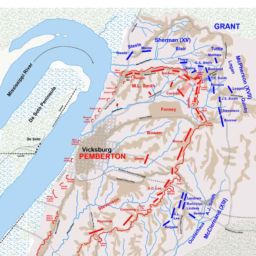

At the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago, June 2–June 8, the party was divided between “Stalwarts,” such as Grant and U.S. senator Roscoe Conkling (1829–1888) of New York, who supported the party’s patronage system, and “Half-Breeds,” such as U.S. treasury secretary and former U.S. senator from Ohio John Sherman (1823–1900), the younger brother of the famous Union Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman, and Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives James G. Blaine (1830–1893) of Maine, both of whom among others contested Grant for the nomination.

Not until the post-World War II political era did partisan primary elections begin to determine presidential, and more indirectly vice-presidential candidates, too, in advance of the Democratic and Republican parties’ national conventions.

At the 1880 Republican Party convention, as was not uncommon in those days and equally so with the Democratic Party, numerous candidates vied for the nomination over the course of multiple rounds of ballots among state delegates. Sometimes, the balloting lasted more than a day. A certain degree of wheeling and dealing transpired behind the scenes, especially as candidates with less support began to bow out and their support was solicited by other candidates’ supporters.

Grant garnered strong but insufficiently conclusive support over the course of 34 rounds of balloting. He awaited word as to each round’s outcome. As was the tradition then, the candidates themselves usually were not present at the convention, relying on their surrogates to make their case for them.

As the balloting wore on, Sherman and Blaine made strong though lesser showings, too, but they were cutting into each other’s support.

After the 35th presidential nomination ballot at the convention, Sherman and Blaine withdrew their names and swung their support to a “dark horse” (unlikely) candidate, James Abram Garfield, a U.S. Congressman from Ohio.

On the 36th round of balloting, James Garfield won the party’s nomination.

Grant was disappointed but campaigned for Garfield against the Democratic Party’s nominee, former U.S. major general Winfield Scott Hancock of Pennsylvania. (Hancock would oversee Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral procession in August of 1885.)

Grant biographer Ron Chernow notes that in campaigning for Garfield, Grant:

again blazed a new path for ex-presidents [like he did with his world tour and in other respects]. Having sat out his own presidential races, he had never campaigned before or made speeches on the hustings and threw himself into the task with self-evident gusto. “We must elect Garfield,” he exhorted a Cincinnati audience. “He is a great man. He has but few intellectual peers in public life.”

. . . . .

As Mark Twain recalled, Grant “was received everywhere by prodigious multitudes of enthusiastic people and . . . one might almost tell what part of the country the General was in . . . by the red reflections on the sky caused by the torch processions and fireworks.”

. . . . .

On October 21, the man renowned for stoic silence squeezed three speeches into one hectic day.

. . . . .

[Grant] was outraged that “our fellow-citizens of African descent” in the South couldn’t vote “without being burned out of their homes, and without being threatened or intimidated.” He would not allow Democrats to “control elections by the use of a shot-gun and by intimidation and assassination.” (905–906)

The U.S. election of 1880 was close. James A. Garfield just barely won the popular vote, however in the Electoral College he beat Hancock handily.

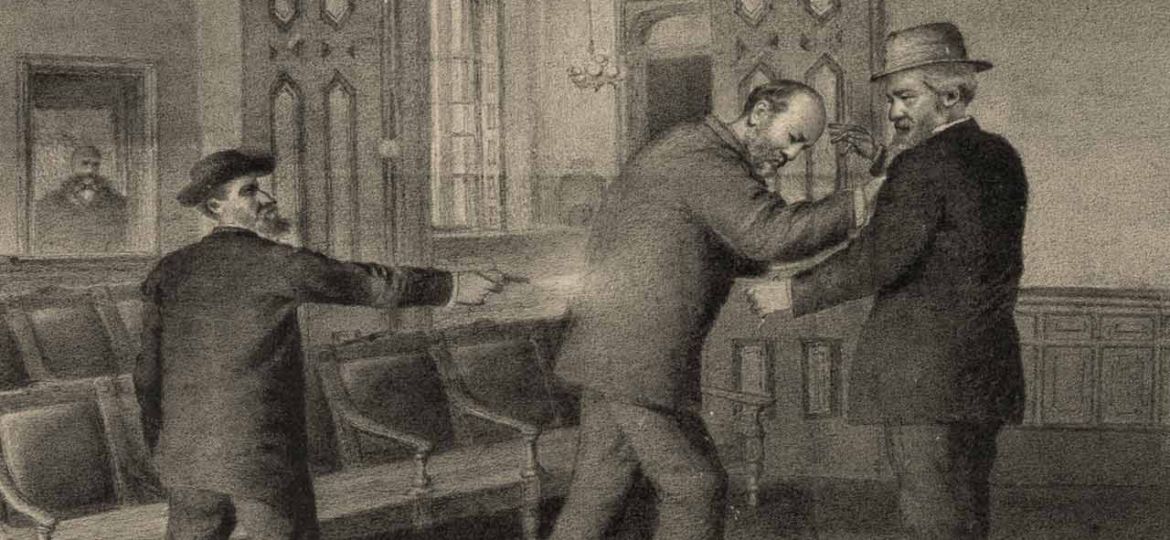

But Garfield’s presidency was to be tragically brief. He was shot by an assassin and died 80 days later from resultant medical complications.

Bret Baier in To Rescue the Republic provides the sad details and context in light of U.S. Grant’s own experiences:

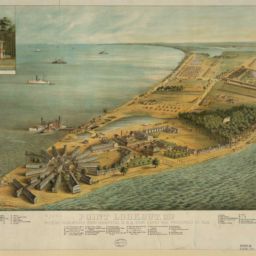

Garfield’s presidency lasted only a few months. On July 2, [1881,] as Garfield was entering [Washington, D.C.’s] train station accompanied by Blaine—who was now secretary of State—a man came up to him and fired two shots, one hitting him in the arm and the other in his back. He fell to the ground.

The assassin was Charles J. Guiteau, from Illinois. He’d been a fervent supporter of Garfield and had even written a speech in praise of him during the campaign. In his twisted view, Garfield owed him his presidency and should have considered him for a plum position. Plagued with resentment, he awoke one night with an inspiration that God wanted him to kill the president so that [Vice President Chester A.] Arthur could step into the office.

It had to occur to Grant that perhaps he’d dodged a bullet for a second time. The prior year Guiteau had made a nuisance of himself with Grant as well, pestering him for an audience when Grant was temporarily living at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City. Grant asked his son Fred if he knew anything about this guy who wanted so much to talk to him.

“He is a sort of lawyer and deadbeat in Chicago,” Fred said. “Don’t let him come up. If you do, he would bore you to death.” Guiteau did manage to get in once, though, and Grant had a hard time convincing him to leave. (306–307)

Politics makes strange bedfellows at times, occasionally friends, but—it seems to me—often makes for at best complicated relationships. After Garfield became president, he and Grant had a falling out, and they ceased communicating with each other. But, as Ron Chernow notes:

Almost as soon as [First Lady] Lucretia Garfield learned of the shooting, Grant knocked at her door [in Long Branch, New Jersey, where she was staying at a hotel], entered quietly, and took her hand. According to one observer, Grant was “so overcome with emotion, he could scarcely speak. . . .” Grateful for Grant’s intervention, Lucretia Garfield later told Julia [Grant that] her husband had been among the first to express sorrow. (910)

Historical and medical consensus today holds that Garfield’s bullet wound, in the back, by today’s standards certainly was not inherently fatal, and possibly could have been survivable relative to even that era’s more limited medical knowledge—maybe, but not necessarily. (See, “A President Felled by an Assassin & 1880’s Medical Care,” The New York Times, July 25, 2006.)

President of the United States James A. Garfield died on September 19, 1881, with the proximate cause of death being complications from sepsis.

Chernow writes:

A shocked Grant received the news at his New York hotel. “You will please excuse me from a consideration of this sad news at this time,” he told a reporter. “It comes with terrible force and is unexpected.” Withdrawing to a private office, Grant wept such bitter tears that Fred Grant said “he had never known him to be so terribly affected.” It must have tormented Grant that he would never have a chance to heal the breach with Garfield, and he was probably reminded of the many death threats he himself had received during his presidency. (911)

ALSO SEE

James A. Garfield National Historic Site. (Website.) “Lucretia’s Holiday Gone Wrong.” Last updated July 22, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/lucretia-s-holiday-gone-wrong.htm.

IMAGES

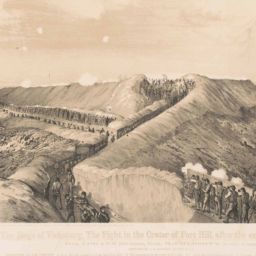

Cropped both as featured and inset above, uncropped below: Mathews, W.T. Scene of the assassination of Gen. James A. Garfield, President of the United States, c. Dec. 21, 1885. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003671706/.

Keppler, Joseph Ferdinand (1838–1894). The Appomattox of the third termers – unconditional surrender / J. Keppler, June 16, 1880. Lithograph. Notation: “Illus. in: Puck, v. 7, 1880 June 16, pp. 266-267.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97515771/. (Puck was a U.S. humor magazine extensively featuring political satire. – S.J.I.)

SOURCES

Baier, Bret. To Rescue the Republic: Ulysses S. Grant, the Fragile Union, and the Crisis of 1876. Custom House, 2021. Kindle.

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Wikipedia, s.v. “SS City of Tokio,” last edited March 11, 2021, at 05:33, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_City_of_Tokio.

_____, s.v. “SS Indiana (1873),” last edited May 14, 2020, at 17:08, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Indiana_(1873).