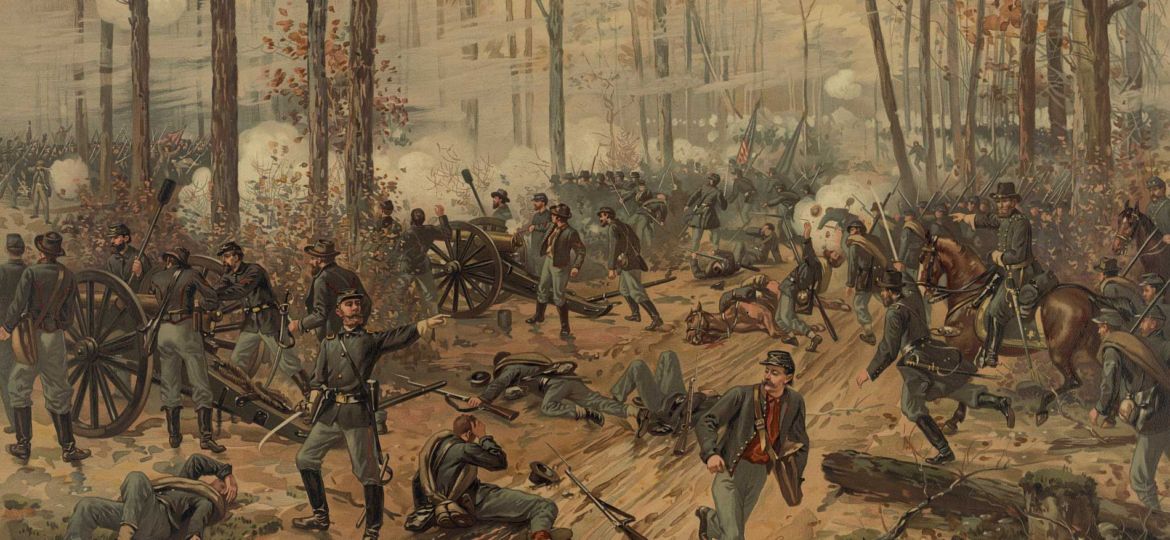

Civil War, Western Theater. 160 years ago today, on April 6, 1862, a Sunday, the two-day Battle of Shiloh erupted—the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War up to that point.

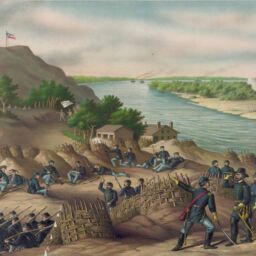

Union and Confederate armies clashed near Pittsburg Landing, a spot on the Tennessee River’s west bank, just inside Tennessee above Mississippi’s extreme northeastern corner.

The battle’s name derives from the simple, wooden, single-room Methodist church, Shiloh Meeting House, around which the battle would rage. In the Hebrew Scriptures, Shiloh is a place of peace, its name connoting something that’s a gift from God.

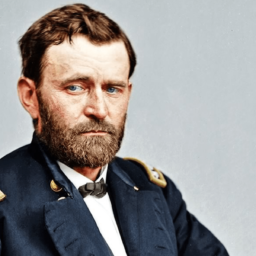

In February 1862, up by Tennessee’s northern border, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant had captured the Confederate forts of Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers respectively. These victories opened up the Tennessee River for Union forces as a path of invasion into the territorial heart of the secessionist confederacy of 11 Southern states.

In the days leading up to the Battle of Shiloh, large portions of Grant’s Army of the Tennessee journeyed southward, up the Tennessee River, to Pittsburg Landing, and bivouacked in the landing’s immediate vicinity. There, they were to await the arrival of elements of the Army of the Ohio, commanded by Major General Don Carlos Buell.

Neither Grant, by this time a major general of volunteers, nor his commanders, including Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman who commanded the Army of the Tennessee’s Fifth Division, anticipated being attacked. Union forces camped in the vicinity were not instructed to put in place various standard defensive measures.

In fact, Grant telegraphed his superior, Major General Henry Halleck, on the night of April 5, “I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack…being made upon us.”1 Even after Union soldiers of the 53rd Ohio Infantry Regiment came in contact with Confederates and its agitated colonel promptly warned Sherman that an attack was be imminent, Sherman replied, “Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There are no Confederates closer than Corinth”—referring to Corinth, Mississippi, more than 25 miles away.2

But, in fact, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston, supported by his second in command General P. G. T. Beauregard, had moved his Army of Mississippi from Corinth to nearly within earshot of the forward-most elements of Grant’s army arrayed around Pittsburg Landing.

Early in the morning of April 6, Beauregard attacked in accordance with Johnston’s battleplan. Aware that Buell’s forces are nearby, Johnston hoped that a decisive assault would prevent a linkup of Grant’s and Buell’s armies, which if combined would significantly outnumber the Army of Mississippi.

Sherman and the other Union senior officers present were completely surprised by the attack. The sounds of artillery reached Grant, 10 miles downstream where he was nursing a badly sprained ankle at his headquarters in Savannah, Tennessee. He rushed to Pittsburg Landing.

As the battle raged throughout the day, Johnston’s Confederates met stiff resistance. Johnston was killed in the fighting, at which point Beauregard assumed command of the Army of Mississippi.

Among several noteworthy moments of the first day, the stalwart, makeshift defense at the “sunken road” portion of the wavering Union line stands out. The position there was held at great cost by the Second and Sixth Divisions, comprised mostly of Illinois and Ohio volunteers who had never before experienced combat.

To break the stubborn Union position, the Confederates massed about 50 cannons and unleashed the largest-yet artillery bombardment in North America’s history. It lasted hours. And eventually the sunken road defense was abandoned.

The day’s Confederate onslaught pushed the Union defenders back everywhere, some by more than a mile, towards Pittsburg Landing—effectively the waters of the Tennessee River itself. But over the course of the late morning and afternoon, Grant and his commanders managed to rally their men, aided by actions such as that determined, bloody stand at the sunken road. By the evening, Grant’s forces had constituted a sufficiently robust defensive perimeter around Pittsburg Landing. As darkness falls, the exhausted Army of Mississippi retired for the night.

In a famously succinct exchange between Sherman and Grant, after the conclusion of the first day’s fighting, Sherman said to Grant, “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” To which Grant replied, “Yes. Lick ’em tomorrow, though.”3

In 1885, Grant in his memoirs described his experience of that July 6–7 night as follows:

During the night rain fell in torrents and our troops were exposed to [a thunder]storm without shelter. I made my headquarters under a tree a few hundred yards back from the river bank. My ankle was so much swollen from the fall of my horse the Friday night preceding, and the bruise was so painful, that I could get no rest. The drenching rain would have precluded the possibility of sleep without this additional cause. Some time after midnight, growing restive under the storm and the continuous pain, I moved back to the log-house under the bank. This had been taken as a hospital, and all night wounded men were being brought in, their wounds dressed, a leg or an arm amputated as the case might require, and everything being done to save life or alleviate suffering. The sight was more unendurable than encountering the enemy’s fire, and I returned to my tree in the rain.4

During the evening of April 6, three divisions of Buell’s army arrived. Those forces were added to Grant’s own army’s reinforcements, in particular his Third Division under Major General Lew Wallace, which arrived belatedly from only five miles away on April 6, after the vast majority of the day’s fighting had ended. As dawn approached and Grant readied his commanders for the next day, Grant’s and Buell’s combined force now overwhelmingly outnumbered the rebel one facing them.

Confederate commander Beauregard remained unware of this reality. On the evening of April 6, he sent a telegraph to Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s president, in Richmond, Virginia, that read: “After a severe battle of ten hours, thanks be to the Almighty, [we] gained a complete victory, driving the enemy from every position.”5

At about 5:30 a.m. on Monday morning, April 7, Grant’s counterattack began. The Union forces numbered about 45,000 men, while Beauregard had about 20,000 on hand. And though defense generally is a force multiplier, Beauregard’s men were exhausted and short on supplies. Conversely, Grant’s reinforcements were comparatively fresh and fully equipped, though to be sure those of Grant’s army who’d fought on April 6 were just as worn as Beauregard’s.

The Union advance was more than the Confederates could bear, and they were forced by mid-afternoon into a general retreat. At day’s end, the Union armies of the Tennessee and the Ohio commanded the field. But with only an hour of daylight remaining, Grant did not order a widescale pursuit of Beauregard.

Shiloh was the costliest-yet battle in American history. Grant wrote in his memoirs:

I saw an open field, in our possession on the second day, over which the Confederates had made repeated charges the day before, so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground.6

The battle’s casualty figures shocked the public of both the North and the South. The Union suffered approximately 1,760 men killed, 8,410 wounded, and 2,885 captured or missing. The Confederate forces lost approximately 1,730 men killed, 8,010 wounded, and 960 captured or missing. Thus, between both sides, nearly 24,000 men were killed, wounded, captured, and missing.

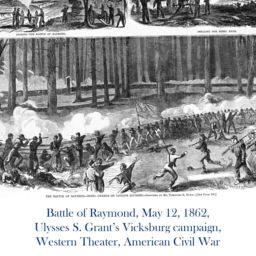

Featured Image: Battle of Shiloh, Thure de Thulstrup (1848—1930), c. 1888, chromolithograph, (Boston: L. Prang & Co.), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540, record at https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92500191/.