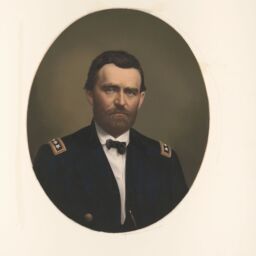

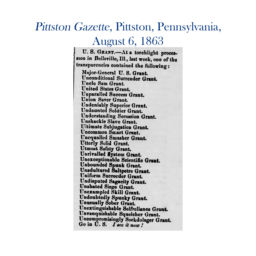

American Civil War, Western Theater, Vicksburg campaign. On July 3, 1863, Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, reached its denouement.

A Dying, Former Neighbor’s White Flag

The Confederate garrison inside Vicksburg was, in the words of its commander Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, “overpowered by numbers, worn down with fatigue.” Under a scorching sun, Confederate General John Bowen, who had been a neighbor of Grant’s in St. Louis before the war, now dying of dysentery, carried towards the Union lines under a white flag of truce a message for Major General Grant. Union General Andrew Jackson Smith met Bowen between the two armies’ lines. Pemberton’s message read in part, “I have the honor to propose to you an armistice for several hours . . . with a view to arranging terms for the capitulation of Vicksburg . . . to save the further effusion of blood.” (Korn 152–153)

To this, U.S. Grant replied in writing:

The useless effusion of blood you propose stopping by this course can be ended at any time you may choose, by an unconditional surrender of the city and the garrison . . . I have no terms other than those indicated above.” (Simpson 259)

In Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, Ulysses S. Grant recorded about July 3, 1863:

It was a glorious sight to officers and soldiers on the line where these white flags were visible, and the news soon spread to all parts of the command. The troops felt that their long and weary marches, hard fighting, ceaseless watching by night and day, in a hot climate, exposure to all sorts of weather, to diseases and, worst of all, to the gibes of many Northern papers that came to them saying all their suffering was in vain, that Vicksburg would never be taken, were at last at an end and the Union sure to be saved. (557)

Grant & Pemberton Meet

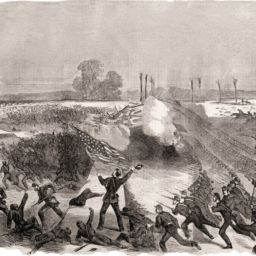

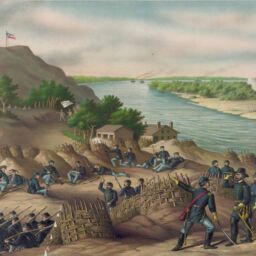

At Bowen’s instigation, Pemberton and Grant agreed to meet at 3:00 p.m. They did so, though Pemberton arrived late. The meeting did not go well, and it was decided that the two commanders’ subordinate general officers try among themselves to reach terms of surrender that both Pemberton and Grant would accept.

Pemberton tried to control his temper; Grant quietly pulled at tufts of grass, an unlit cigar in his mouth. But the other generals did no better at structuring an agreement. Grant rejected Bowen’s proposal to allow the [Confederate] garrison [in Vicksburg] to march out, complete with small arms, artillery, and all the honors of war. Pemberton concluded that the question of terms was up to Grant; Grant replied that he would contact Pemberton that evening.

. . . . .

It was evident that to ship some thirty thousand [Confederates] to prison camps in the North might be more than the Union navy could handle. . . . The only alternative appeared to be to parole the garrison; that is, disarm it and send it away with the assurance that these men would not return to duty until exchanged just as if they were prisoners. . . . Later [Grant said] that he believed that “consideration for their feelings would make them less dangerous foes during the continuance of hostilities, and better citizens after the war was over.” [Grant] sent off the proposal to Pemberton and waited. Several hours later, [on July 4,] he had his reply. After reading it, he sighed, then said calmly, “Vicksburg has surrendered.” (Simpson 260-261)

Thus, in the end, Grant decided not to insist on unconditional surrender as he had famously done at Fort Donelson.

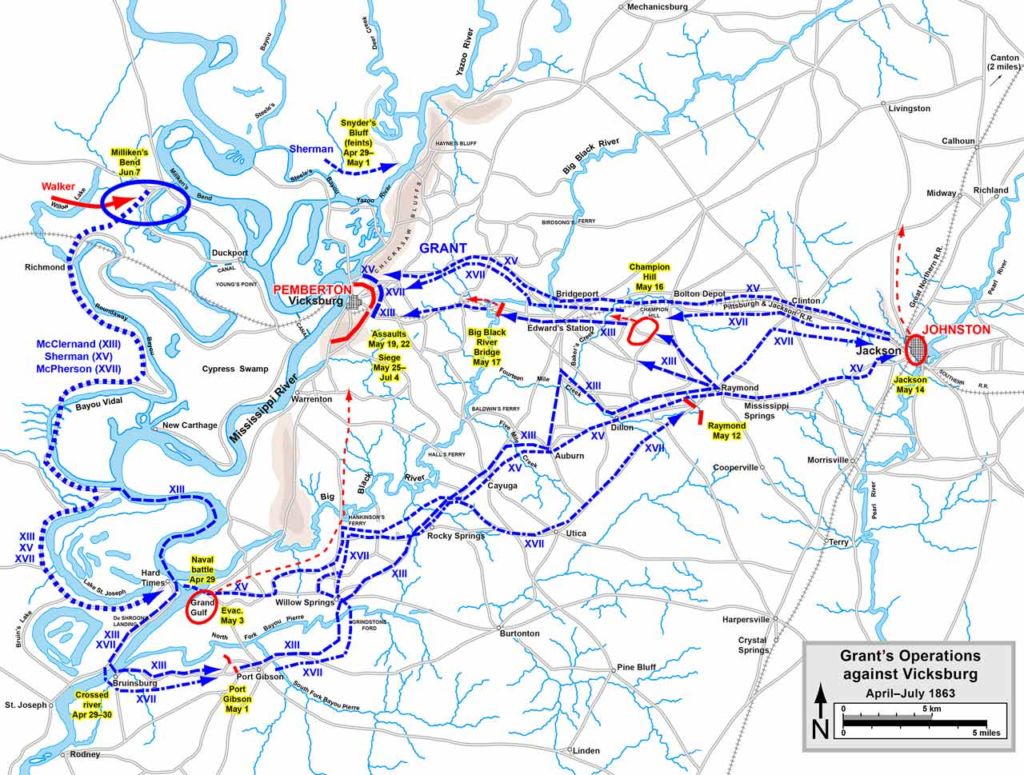

Ulysses S. Grant’s Daring Vicksburg Campaign in Mississippi

Grant’s Vicksburg campaign is without a doubt among the greatest and most important of the American Civil War. In late April 1863, General Grant, with about 33,000 available men, outnumbered 2 to 1 by the Confederate forces in Mississippi, carried out an amphibious landing to cross the Mississippi River, from Louisiana, south of Vicksburg, without any dependable means to supplying his army and with no practical route of retreat if he should need it. Of Grant’s men at the time, only about one third could be carried by the Federal transports in the first wave. (Korn 84)

The daring crossing was accomplished, after which Grant undertook a daring route to Vicksburg. He decided to thrust northeastward into Mississippi’s interior first, moving and fighting along an oblique route away from Vicksburg—in effect pushing one group of Confederate forces away from Vicksburg and making it unable to link up with the second main Confederate force, under General Pemberton near Vicksburg. Grant would then turn his army around and head back westward towards Vicksburg to tackle Pemberton’s army.

Only Interior Communicability

Grant’s gambit required breaking away from his army’s “lines of communication”—(a phrase of military parlance meaning routes for supplies, reinforcements, and communication, such as pathways to distant depots, other armies, higher headquarters, capitals, etc., in contrast to “interior lines” that exist within an army’s own zone of control).

Grant’s Army of the Tennessee would need to move fast, forage for food, and scrounge and improvise for materiel and anything else required.

Despite these risks, Grant’s army won a rapid series of victories against Confederate forces. After the Battle of Raymond (May 12), Grant captured the capital of Mississippi at the Battle of Jackson (May 14). He then won battles at Champion Hill (May 16) and Big Black River Bridge (May 17).

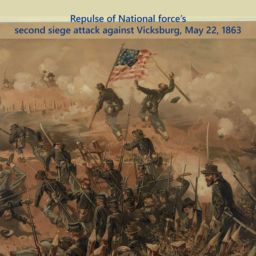

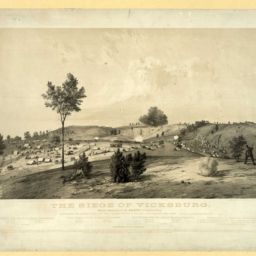

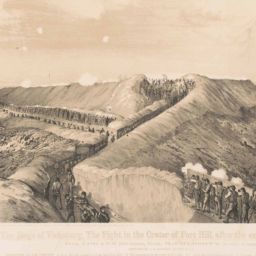

The latter two Union victories forced Pemberton’s Confederates to retreat into Vicksburg. Grant then settled into a siege of the river-port town after assaults against it failed on May 19 and May 22. Though the May 19 attack arguably served to consolidate Grant’s lines in a stranglehold on Vicksburg, the May 22 assault accomplished nothing that justified the cost. Grant in his memoirs admitted to regretting the May 22 assault, saying that only his June 3, 1864, assault at the Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia, was a bigger mistake. (Grant 276)

“The Father of the Waters Again Goes Unvexed to the Sea.”

On July 9, after hearing of Grant’s victory at Vicksburg, Major General Franklin Gardner surrendered his Confederate under siege at Port Hudson, Louisiana, the only remaining insurrectionist stronghold on the Mississippi River.

With the Mississippi completely in Union control, thanks largely to Grant, and navigable by Union forces without impediment, the interior of the main, eastern bulk of the confederacy of Southern, rebellion states had been cut off from Texas and Arkansas, which supplied the livestock and horses that Confederate armies east of the Mississippi River badly needed. (Chernow 292)

Upon hearing of Port Hudson’s capture, President Abraham Lincoln declared one of the immortal phrases of the American Civil War: “The Father of the Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” (Letter to Conkling)

IMAGE

“Interview between Grant and Pemberton,” in Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, Alfred H. Guernsey and Henry M. Alden. Chicago: The Puritan Press Co., c. 1894, v. 2. Print, wood engraving. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003663125/.

Map, see below: Jespersen, Hal. Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War.

SOURCES

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

Grant, Ulysses S. Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. 2 Vols. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102138632?type%5B%5D=all&lookfor%5B%5D=personal%20memoirs&ft=ft.

Korn, Jerry. War on the Mississippi: Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books Inc., 1985.

Lincoln, Abraham. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 6. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Letter to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln6.

Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, (Military Classics). Zenith Press, 2014. Kindle Edition.