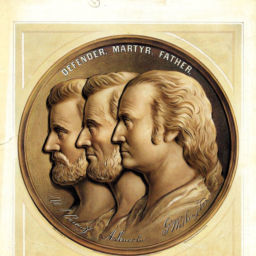

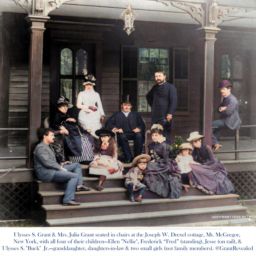

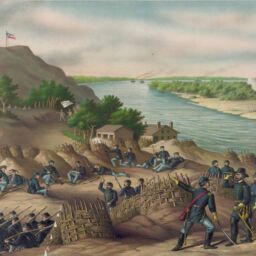

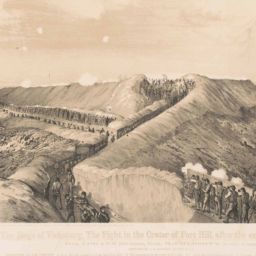

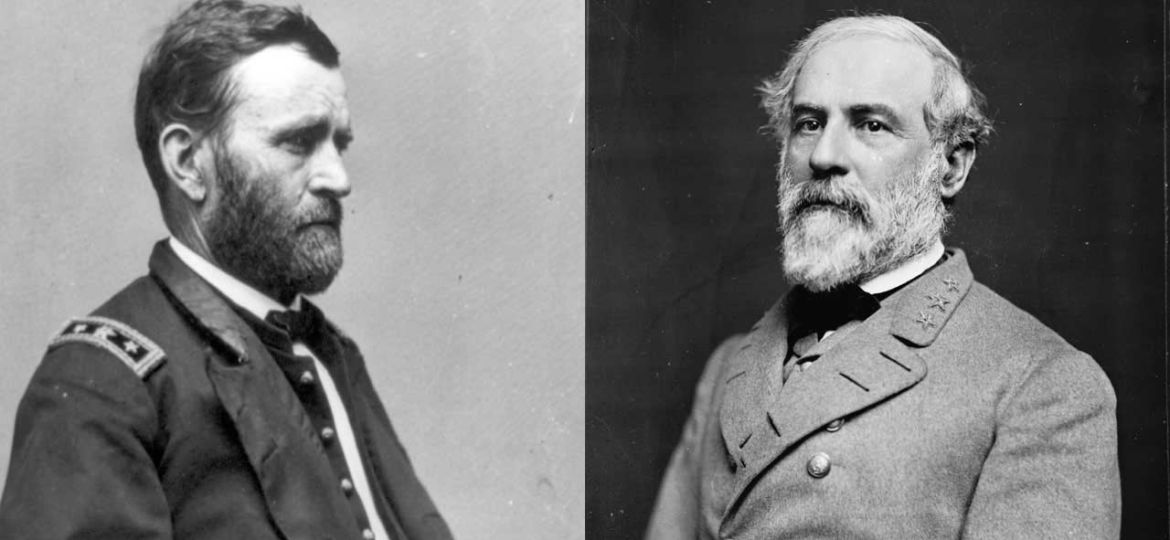

Washington, D.C. On June 20, 1865, President Andrew Johnson asked the U.S. attorney general James Speed to order the U.S. attorney in Norfolk, Virginia, to abandon the prosecution for treason of Robert E. Lee, the former commander of the grandest army of the confederacy of Southern states in rebellion during the Civil War (1861–1865).

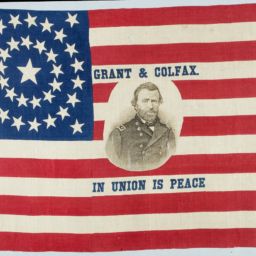

Johnson likely issued his presidential request with reluctance. And it was Ulysses S. Grant, commanding-general of the U.S. Army that had defeated Lee on April 9, 1865, who forced Johnson’s hand by threatening to resign if Johnson did not end the prosecution case against Lee.

Today, President Andrew Johnson is generally remembered for his impeachment by the U.S. House of Representatives, his racist opposition to citizenship and voting rights for former slaves, and his opposition to Congressional Republicans’ more radical Reconstruction policies for the 11 Southern states that had been in rebellion.

But Johnson was also a strong Unionist. He was a native of Kentucky and had been a Democrat when Southern pro-slavery states strongly aligned with the Democratic Party. Johnson owned five slaves. Then in 1863, he freed them. But as Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ron Chernow points out, Johnson did so “as part of his vendetta against the slavocracy,…not from any real regard for those in bondage. ‘Damn the Negroes,’ he insisted, ‘I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters’” (531–532).

Johnson was the only U.S. senator from a secession state who, courageously, remained loyal to the United States during the Civil War (550).

In 1864, Johnson accepted a spot on the Republican Party’s ticket as vice-presidential candidate with Lincoln running for reelection as U.S. president. Following President Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, Johnson became the 17th president of the United States.

President Johnson wanted to take a hard line against the leaders of the Southern Confederacy. However, his hardline approach conflicted with the amnesty arrangement that Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant included in his terms of surrender imposed on Robert E. Lee at Appomattox in April 1865. President Lincoln approved those terms. Now Johnson wanted to nullify them.

And so Grant confronted Johnson regarding the plan to prosecute Lee. In his book Around the World with General Grant (1879), John Russell Young relates Grant’s summary of the dispute with the president:

Mr. Johnson spoke of Lee, and wanted to know why any military commander had a right to protect an arch-traitor from the laws. I was angry at this, and I spoke earnestly and plainly to the President. I said, that as General, it was none of my business what he or Congress did with General Lee or his other commanders . . . That did not come in my province. But a general commanding troops has certain responsibilities and duties and power, which are supreme. He must deal with the enemy in front of him so as to destroy him . . . His engagements are sacred so far as they lead to the destruction of the foe. I had made certain terms with Lee . . . If I had told him and his army that their liberty would be invaded, that they would be open to arrest, trial, and execution for treason, Lee would never have surrendered, and we should have lost many lives in destroying him. Now my terms of surrender were according to military law, and so long as Lee was observing his parole I would never consent to his arrest . . . I should have resigned the command of the army rather than have carried out any order directing me to arrest Lee or any of his commanders who obeyed the laws. (Chernow 552-553)

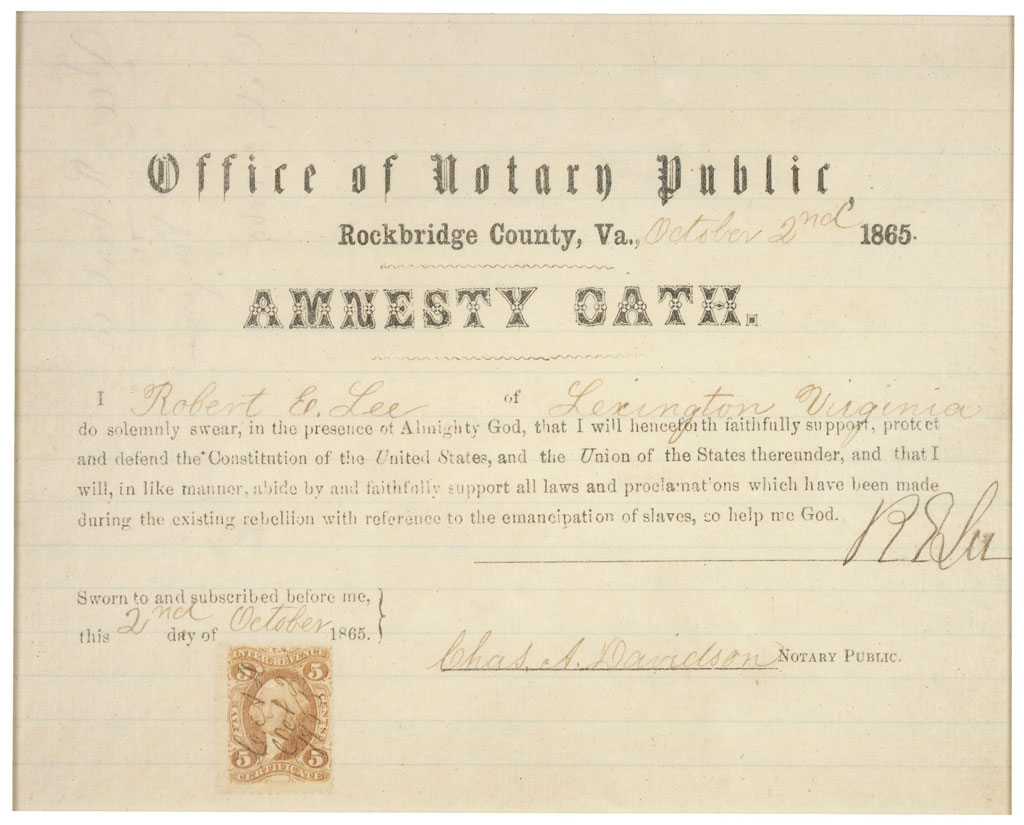

President Johnson backed down. Lee never faced prosecution. Having accepted Grant’s amnesty terms at his surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Lee officially took the amnesty oath, on October 2, 1865, swearing to:

faithfully support, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States, and the union of the States,… and…abide by and faithfully support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion with reference to the emancipation of slaves. So help me God. (“Proclamation”)

SOURCES

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Kindle.

“President Andrew Johnson: Amnesty Proclamation (1865).” Tennessee Secretary of State website. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://sharetngov.tnsosfiles.com/tsla/exhibits/blackhistory/pdfs2/1865%20Johnson’s%20Amnesty%20Proclamation.pdf.

IMAGES

Library of Congress and National Archive.